Putin’s Ukrainian adventure has Europeans talking about nuclear power as if their existence depends on it. Threaten to deprive people of access to reliable and affordable energy and the love affair with wind and solar is soon forgotten.

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to explain the relationship between total collapses in wind and solar output and sunset and calm weather.

True enough the political intelligentsia have done all they can to have the masses believe otherwise but, anticipating that the mob will surely revolt if left freezing in the dark for any length of time, the focus is now on power that can be delivered on-demand, come what may.

Following Europe’s Big Calm, when wind power output barely registered for months, the French President announced a wholesale reversal of their anti-nuclear power plant policy, no doubt driven by the need to ensure that they will never suffer embarrassing power shortages like their British and German neighbours. Macron made it crystal clear that France would invest heavily in their existing nuclear power plants and build 14 next-generation nuclear plants, adding to the 56 plants currently operating and providing the French with over 70% of their power needs, at a cost roughly half that being paid by their wind and solar ‘powered’ German neighbours.

Faced with the reality of actually trying to rely exclusively on wind and solar, even Germany’s Greens are talking about maintaining their ability to produce coal-fired and nuclear power for the foreseeable future.

Renewable energy rent-seekers naturally hate nuclear power and do everything in their power to make sure the proletariat are scared stiff at its very mention. Hysterical hype about nuclear meltdowns and radiation clouds are all part of their self-serving narrative.

Harry Stevens, however, is ready, willing and able to present nuclear power for what it is: the safest way of generating affordable electricity that does not depend on the weather or time-of-day.

Who’s afraid of nuclear power?

The Washington Post

Harry Stevens

28 April 2022

A neutron is hurtling through space. It is heading for an atom, whose nucleus absorbs the neutron and splits, releasing more neutrons, which split more atoms, and on and on and on.

This is a fission chain reaction. It is a series of events, one leading inexorably to the next, with a predictable consequence: the release of tremendous energy.

Here is another, less predictable, series of events. Eleven years ago, the mightiest earthquake in Japan’s recorded history pushed forth a 49-foot tsunami that flooded the backup electricity generators at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. With no electricity, the workers at the plant could not control the cooling water, and the reactor’s core melted. Tsunamis pose no risk to Western Europe, but two months after the earthquake, the German government decided it was done with nuclear power.

The decision marked a dramatic reversal for then-Chancellor Angela Merkel, a former scientist who had declared a few years earlier, “I will always consider it absurd to shut down technologically safe nuclear power plants that don’t emit CO2.”

As Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine in February, the consequences of that “absurd” reversal only deepened. Over the past decade, Germany phased out most of its nuclear plants and scheduled its last three to power down this year. That has increased the country’s reliance on natural gas, most of which it buys from Russia.

Many have urged Germany to join the United States in boycotting Russian energy, saying the purchases are tantamount to supporting “Putin’s war machine.” But Merkel’s successor, Chancellor Olaf Scholz, has refused, saying such a ban would be disastrous for the German economy.

This is one of the costs of nuclear fear: depending on a dictator to keep your lights on.

Fear is the future’s tollbooth, and it can collect its fee in surprising ways. After 9/11, more people than expected began to die in car accidents on U.S. freeways, multiple studies found. People scared of the vivid threat of a midair terrorist attack apparently opted for the statistically more dangerous behavior of long-distance driving.

Likewise, lots of people are scared of nuclear waste, which can be stored safely or reprocessed into useful things such as medical isotopes. The byproducts of coal-fired plants pose a more imminent threat. Following Germany’s nuclear phaseout, an estimated 1,100 additional people died each year from inhaling the poisonous gases and particle pollution from the coal plants Germany used to temporarily replace its nuclear ones.

There is another, longer-term cost of nuclear fear. Germany has pledged to sharply reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to help slow global warming; it built thousands of wind turbines and solar arrays to wean itself off fossil fuels. But claiming to be serious about fighting climate change while powering down nuclear power plants is a bit like leaping into the ring to fight Tyson Fury without boxing gloves on. Talk as tough as you like, but people might wonder whether you’re serious about winning.

“If you were designing a truly rational energy system to move towards a zero-carbon energy system, this is not the path you’d be taking,” Randy Bell, senior director for global energy security at the Atlantic Council, said of Germany’s decision to abandon nuclear power.

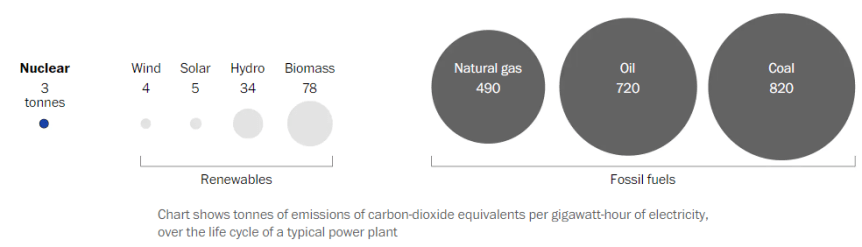

Even accounting for emissions created during the building of the facility and the mining of its fuel, the typical nuclear plant produces fewer greenhouse gases than power plants fueled by natural gas and coal, and about the same as those running on renewable sources such as wind and solar.

Yet on windless days, wind turbines fail to spin, and even in sunny places, solar panels sit idle at night. Nuclear plants make electricity all day long. As the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a group of 278 top climate experts assembled by the United Nations, put it, “Nuclear power can deliver low-carbon energy at scale.”

What gets in the way? “Emotional factors” can make nuclear energy politically toxic, the report noted, citing Germany’s policy after Fukushima. The conclusion? “Nuclear power and accident potential score high on psychological dread.”

________________

Around the time Germany was deciding to power down its nuclear plants, Josh Wolfe’s company was prospering. In 2008, Wolfe and his business partners founded Kurion, named after Marie Curie, and developed a novel method for sealing nuclear waste in glass. After the Fukushima accident, Kurion scored a major contract to help clean it up. A few years later, Wolfe’s venture capital fund sold its stake to the French conglomerate Veolia for an enormous profit.

Wolfe likes to invite people to imagine an alternate reality, one in which nuclear fission was discovered in, say, 2018, rather than in 1938, and it was first used to power cities, rather than to destroy them. “If atomic energy was discovered today, people would be like, ‘Oh my God, this is magic,’ ” Wolfe said. The days of depending on dictators to light up our homes would be behind us, and a future with less air pollution would lie ahead.

Back in the real world, most people first learned of nuclear fission as a way to destroy an entire city in the blink of an eye. In the decades following the American bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the United States and the Soviet Union secretively developed and tested increasingly menacing weapons while openly speculating about how and when to use them on each other.

This violent history has made us like a man who is afraid of dogs because one bit him as a boy. Show him a golden retriever wagging its tail, and he sees a Rottweiler gnashing its teeth. Show us a nuclear power plant, and we see a mushroom cloud. But though they harness the same property of nature — the nuclear chain reaction — nuclear power plants and atomic bombs are separate technologies. “So I got to thinking,” Wolfe said, “this needs a rebrand.”

Last July, Wolfe shared his idea on Twitter, complete with a new name: elemental power. “Elemental” would not only shed the stigma of “nuclear” and its association with bombs and radioactive fallout, but it would also emphasize the fact that the technology takes advantage of a natural process, just like solar and wind.

Most power plants, including nuclear power plants, convert rotating energy into electricity using Michael Faraday’s discovery that electrons will flow through a wire when a nearby magnet moves. A great deal of the planet’s energy challenges hinge on how we solve this seemingly simple engineering problem: getting a turbine to spin and keep spinning.

Of course, you could spin the turbine yourself, but you won’t produce much power, and you’ll soon grow tired.

The trick, then, is to get something to flow through the turbine. If you have a river, you can put the turbine in it — the world gets about a sixth of its power that way — but you might disrupt the river’s ecosystem. You can also set the turbine up high and wait for the wind to blow, an increasingly popular method that contributes about 7 percent of global electricity.

But the most common way to spin a turbine is to pump steam through it. Coal and natural gas plants make steam by burning fuel to boil water. When fossil fuels burn, they produce greenhouse gases and pollute the air.

Nuclear power plants make steam, however, by using the heat energy from fissioned atoms to boil water. Most atoms do not fission, but the isotopes of certain elements, such as uranium-235, are fissile.

This explanation vastly oversimplifies a great deal of sophisticated engineering. However, the basic concept of a steam-powered electricity plant had been worked out by the late 1800s. “The only thing the 20th century gave us was a new way to make steam by heating it with nuclear fission,” said James Mahaffey, a retired nuclear engineer who has written several books on nuclear energy.

Still, it would be hard to dream up a tougher assignment for a public relations pro than rehabilitating nuclear power’s image. Nuclear fear is everywhere. It is in the villainous Mr. Burns’s rat-infested power plant, where Homer Simpson nods off in the control room, and toxic sludge pours into the local river. It is in monster movies such as “Godzilla,” disaster movies such as “The China Syndrome” and horror movies such as “Chernobyl Diaries.” After decades of relentless anti-nuclear messaging, the very idea of radiation — invisible, mysterious, carcinogenic — is terrifying.

Not all radiation, of course. Go to a beach on clear summer day, and there are your fellow humans basking in it. Melanomas and other skin cancers, most of which are caused by exposure to ultraviolet rays in sunlight, killed an estimated 118,900 people in 2019.

The official death toll from radiation at Fukushima, for comparison, stands at one, although over 100,000 people were evacuated from the area as a precaution, and some 2,000 died in that chaos.

Why are we more afraid of nuclear power plants than the sun? “We are specifically afraid of the radiation sources that are human-made,” said David Ropeik, an author and risk communication consultant.

That widespread fear is similar to that of vaccines, he said: “Mom’s saying, ‘I’d rather my kid get the natural disease like measles than the vaccine.’ Risk will always be how we feel about the facts, not the facts alone.”

__________________

Mahaffey can measure the cost of nuclear fear by how easily he can buy laboratory equipment off eBay for the experiments he does in his basement. (Right now he’s trying to confirm the existence of quantum entangled gamma rays from europium-152.) He recently bought a spectroscopy amplifier that used to be owned by North Carolina State University, and his linear gate stretcher was formerly the property of Arizona State University.

“It’s heartbreaking to see the stuff you can now buy for pennies on the dollar that should be used for instruction and research into nuclear topics,” Mahaffey said. “Nuclear topics used to be a big thing, and they’re not anymore.”

Mahaffey got his PhD in 1979, the year a reactor at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant partially melted down. As with Fukushima, the public reaction was out of proportion to the dangers — no one was hurt, and the inert gases released from the reactor posed no health risks to humans. But that accident marked a turning point for the U.S. nuclear industry.

“I saw it disappear over the horizon,” Mahaffey said.

As more safety regulations were introduced, nuclear plants became more expensive to build, and power companies found it increasingly difficult to justify those costs.

In the United States, nuclear energy’s advocates for decades have been awaiting a renaissance that seems to never come. Public opinion remains mixed, but younger adults are less favorable to nuclear power plants than older people, according to polling from the Pew Research Center.

But a new generation of environmentalists is beginning to challenge the anti-nuclear dogma of its activist forebears. “You’re hard-pressed to find an issue where Bernie Sanders and I disagree, and this is one of them,” said Marcela Mulholland, 24, political director for Data for Progress, a left-leaning think tank, speaking of the senator from Vermont. “I think it just speaks to a generational divide, where these older people who were politicized and active in the ’70s are sometimes the most anti-nuclear people.”

On the political left, home to most environmentalists, people like to say that a dollar spent on a nuclear plant is a dollar not spent on a wind turbine or a solar panel. Mulholland used to buy that argument, but not anymore.

“Where I’m at now is, if it’s true that the climate crisis is as big of a problem and as serious and urgent of a threat as folks say it is, then we need to be really ruthless and rigorous in thinking about how we can reduce emissions in the most effective and quick way possible,” she said.

When activists succeed in shutting down nuclear plants, greenhouse gas emissions increase, she said, pointing to the closure of the Indian Point nuclear plant in New York state, after which carbon-dioxide emissions jumped.

The electricity sector accounts for less than half of global greenhouse gas emissions, and although nuclear reactors have powered submarines for decades, ideas such as nuclear-powered planes and automobiles remain, for now, in the realm of science fiction and ill-fated military experiments. But as more people switch from vehicles powered by gas to those powered by electricity, it will be all the more crucial for the electric grid to run on a fuel that does not exacerbate the problem of global warming.

Mulholland and other young, like-minded environmentalists favor maintaining existing nuclear plants while supporting the development of next-generation nuclear technologies such as small modular reactors, which advocates say are safer and less expensive than the current generation of nuclear reactors.

Seaver Wang, 29, can tell you the exact moment he changed his mind about nuclear power. In 2010, as a senior in high school, he had already been admitted to a few colleges and was trying to decide which one had the best environmental science program for him. The day he went to visit Cornell, James Hansen, perhaps the world’s most famous climate scientist, was giving a talk, “so I dragged my entire family there,” Wang said.

Before that talk, Wang said, “my opinions on clean energy were very sort of vanilla.” Fossil fuels were bad. Wind and solar were good. Nuclear energy was clean but dangerous and expensive. But Hansen explained that nuclear power generation was about to become even cheaper and safer with the advent of newer technologies. “That was really sort of a shifting moment for me on the issue of nuclear power,” Wang said.

Wang ended up at another Ivy League school, the University of Pennsylvania, and went on to get a PhD in earth and ocean sciences at Duke while still participating in environmental activism. In 2014, he was arrested outside the White House protesting the Keystone XL pipeline.

Wang believes we are at the dawn of a new atomic age. Just last week, the Biden administration pledged $6 billion to save financially strapped nuclear power plants, framing the decision as a part of the administration’s strategy to fight climate change. China and Russia are building new reactors, and Britain is funding small modular reactors as it struggles to eliminate carbon emissions. Even France, which already gets about two-thirds of its electricity from nuclear plants, is planning a “rebirth” of its nuclear industry.

But even if the world eventually embraces power, the margin for error will be razor thin. When a coal mine collapses or a natural gas pipeline leaks, the public ignores it or quickly moves on. But if anything goes wrong with reactor, no matter how minimal the damage, nuclear fear will reignite, with severe consequences for the industry.

Much has been made in recent weeks of Ukraine’s 15 reactors, eight of which remain active. Even in a war zone, these reactors pose little risk. Their containment structures are built to withstand a plane crash and to seal in radioactive gases, should they somehow lose power.

“Even in a worst-case scenario, there would be no release of radiation to the public,” according to a report from the Breakthrough Institute, the think tank focused on technological solutions to environmental problems where Wang has worked since 2019. Still, the very existence of Ukraine’s power plants engenders fearful memories of the catastrophe at Chernobyl, even though the somewhat ill-conceived graphite-moderated nuclear reactor that melted down in 1986 bears little similarity to the pressurized-water reactors currently operating in Ukraine.

Back in Germany, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine provoked a brief reassessment among the country’s leaders about the decision to abandon nuclear power. Scholz declared Germany “must change course to overcome our dependence on imports from individual energy suppliers.”

Asked if that meant extending the life of the three German nuclear plants still producing power, Germany’s economy minister said that nothing was off the table. But just nine days later, the German government clarified that it would not be changing its mind about nuclear power.

Wang thinks that decision might well prove temporary. “Nuclear energy is here to stay,” he said. As for those who oppose nuclear power? “They’ve lost,” he said, “but just don’t know it yet.”

The Washington Post

Nuclear “waste” isn’t just “useful medical isotopes.” It’s actually valuable 5%-used fuel. Unused fuel needs 300,000 year custody. Fission products need 300 year custody. Read “Smarter Use of Nuclear Waste” in December 2005 Scientific American (online). We know how to make inherently safe reactors. Read “Plentiful Energy” by Charles E. Till and Yoon Il Chang. See http://vandyke.mynetgear.com/Nuclear.html for links.

Actually, only 9.26% of fission products need 300 year custody. 0.45% need 100 year custody. Half the rest are innocuous before thirty years, and the remainder isn’t even radioactive.

How fast are fission products produced? One tonne per gigawatt year. 9.26%, or 92.6 kilograms of long-term waste per gigawatt year. How much is a gigawatt year, in familiar terms? 8,766,000,000 kilowatt hours. There really is no problem.

A half goodish article.

Nuclear is safe. Read Robert Zubrin’s Merchants Of Despair.

CO2 is safe. Read Dr. Tim Ball’s Human Caused Global Warming The Biggest Deception In History.

John Doran.

Which half troubled you?

The demonisation of CO2.

It is not only safe, it is essential to ALL life on Earth, & has near zero effect on climate.

Website: principia-scientific.com

That’s not down to STT.

For me it was the inherent assumption in the article that it is natural for people to treat nuclear incidents more seriously.

“When a coal mine collapses or a natural gas pipeline leaks, the public ignores it or quickly moves on. But if anything goes wrong with reactor, no matter how minimal the damage, nuclear fear will reignite, with severe consequences for the industry.”

This is not a natural reaction. It is a carefully nurtured public reaction created with propaganda and purposeful media attention. When those other accidents happen, no one keeps them in the media for years afterwards.

Most people don’t even know that natural gas killed eight people and demolished a neighborhood in San Bruno in 2010.

When folks mention natural gas in policy based articles, no one feels compelled to include a statement like, “despite the San Bruno disaster” or similar, but few journalist mention nuclear without adding some reference to Fukishima or 3-mile Island.

How many folks even know about the petroleum refinery just miles down the coast from the Japanese nuclear plant which caught fire for days and spewed toxic chemicals across the land, into the sea and into the air. Pictures of it burning were intentionally mislabeled as the nuclear plant in some publications.

Yet, no one is talking about the refinery owners’ negligence for not building a higher seawall.

Also, new SMRs may be cheaper to build, but they also produce vastly less electricity. Estimate still have them producing electricity at a higher cost that “traditional” plants. True, you won’t need as large an up-front capital commitment before you’re selling electricity, but your unit price will be higher.

It’s pointless that SMRs are “safer” than current plants. Current plants are safer than any other source of energy including wind and solar. Deaths from falling off wind turbines and solar roofs far out pace any casualties from nuclear. How much safer than “safe” does one need to be? At these levels the difference is meaningless.

Finally, the claim that one person died of radiation from Fukishima is utterly false. One worker later died of cancer, almost certainly from other causes or from smoking. They allowed it to be blamed on Fukishima as a kindness because his family received more benefits.