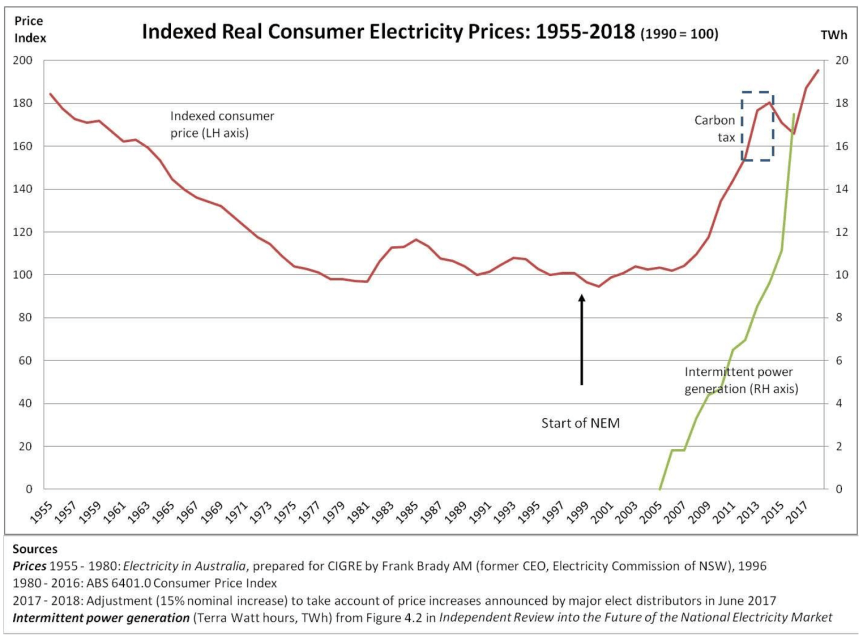

Politics is a cruel caper, at the best of times. And, in Australia, power politics is merciless. A decade and-a-half of government intervention in the power market has left Australia with the highest power prices in the world and a grid on the brink of collapse.

The disaster is largely down to distortions caused by the Large-Scale RET – through which $15 billion in subsidies has already been thrown to the wind and sun, with a further $45 billion to be squandered to the same ends – which has rendered cheap and reliable conventional generators unprofitable. The risk of the more populous States – Victoria, NSW and Queensland – following South Australia into Stone Age gloom every time the wind stops blowing has focused attention on the idiocy of attempting to rely upon the weather for power.

In the week just gone, Australia’s PM, Malcolm Turnbull, determined to bet his hold on the House by launching what has been termed the ‘National Energy Guarantee’ (NEG). In street slang, short for ‘negative’, an unfortunate acronym, if ever there was one.

What is really intended is a Network Reliability Standard, which will be policed by an overarching Federal watchdog, the Energy Security Board, much like Banking and Corporations regulators, APRA and ASIC. For example, the Australian Potential Regulatory Authority ensures that banks hold a minimum reserve of capital to satisfy depositors’ demands for their funds. The Australian Securities and Investment Commission, regulates the conduct of directors in charge of companies. Pundits and commentators are having a hard time working out what the NEG means for Australia’s power market.

STT’s Canberra operatives have given us the inside running on what’s really in play. We’ll come to that in a moment. However, amongst commentators, yet again, it’s Judith Sloan who gets closest to the mark.

If we can’t have a RAT, a NEG is as good as it gets

Judith Sloan

The Australian

18 October 2017

Thank god the clean energy target is gone; it was just another version of the renewable energy target that involves massive subsidies for the intermittent renewable energy sector.

I was rather hoping for a RAT — a reliable and affordable target, but instead we have the national energy guarantee. On the face of it, the NEG is much better than the CET.

One of the biggest downsides, however, is that the RET will be allowed to run for another two years for new investment and the certificates will continue to be traded until 2030. This is a hangover that the government should have sought to avoid.

Mind you, imposing reliability requirements on new and existing renewable energy installations will reduce the returns for investors in the renewable energy sector. Expect some loud and unrelenting complaints from them in the coming weeks.

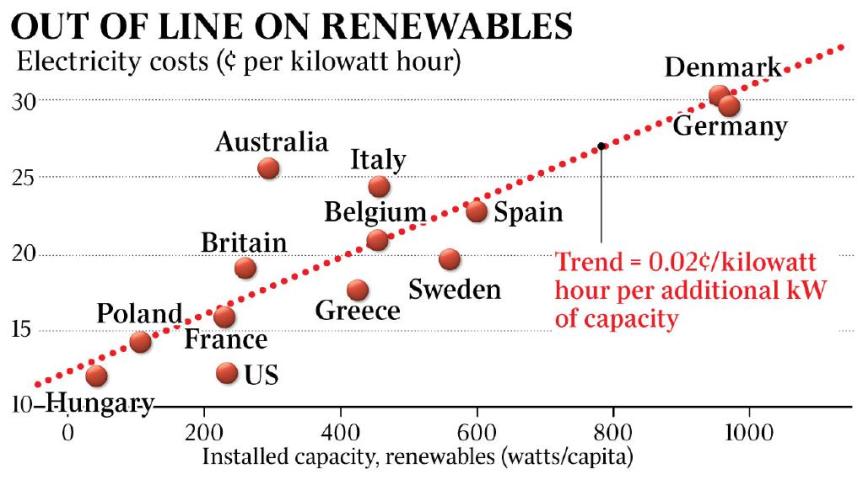

But note that there is an almost perfect correlation between the extent of renewables in electricity generation and prices. Check out the chart. The countries with loads of wind farms and solar panels have the highest electricity prices.

It’s hardly surprising. Because of their intermittent nature, there is a requirement for back-up and back-up costs money. It can take the form of under-utilised synchronous power plants — nuclear (although not in Australia), coal, gas, hydro — or expensive, short-lived batteries.

(Surely, the South Australian government is not serious about the ongoing use of diesel generators.)

Either way, you are inserting into the system higher fixed costs that have to be paid for, one way or another. When you add the problem of intermittency to the challenge of demand peaks you set the scene for a system that is inherently unstable.

Indeed, the chief of the Australian Energy Market Operator alluded yesterday to the problems it is having keeping the South Australian electricity market producing enough power to meet demand. Just last week, one of the operators was ordered to fire up to deal with the stress on the system.

The NEG does away with subsidies for renewables and the associated certificates and instead imposes reliability and sustainability requirements on electricity retailers. Every megawatt of intermittent electricity will need to be offset with a megawatt of reliable electricity. Failure to do so will lead to the imposition of fines or, in the worst-case scenario, cancellation of the licence to operate. The retailers will take this seriously. The definition of reliability will be important but this is an important development.

The expectation is that this arrangement will create an incentive for investment in new, reliable supply, in particular, which can drive down prices. This won’t necessarily take the form of new high-efficiency, low-emissions coal plants, although that would be great. But to have our existing coal plants properly maintained and extended would be a useful outcome.

New gas plants would also be welcome. As for meeting the emissions reduction targets, the government is taking the sensible decision to back-load the commitment to reduce emissions by 26 per cent by 2030 above 2005 levels. With technology improving and the costs coming down, it is entirely reasonable to delay the heavy lifting to the years just before 2030.

Note that providing for the purchase of (cheap) overseas carbon credits will also prove a useful role in the package as this option will provide a cap on local abatement costs.

There is still a lot of water to flow under the bridge. The reaction of the states will be important; their policies can distort the workings of the National Electricity Market. It will be necessary to land on a common understanding of what is required of all the participants.

But the fact the key electricity regulators are on board provides a degree of confidence that it can work. Let’s just hope that it’s given a fair chance.

The Australian

Judith followed up with this piece in the Weekend Australian.

I Guarantee This: Politics is at Play with Cheap Power

The Australian

Judith Sloan

21 October 2017

There’s a simple way to bring down energy prices, but the Coalition’s policy isn’t it.

The National Electricity Guarantee announced this week is an exercise in political economy. If you simply were interested in ensuring cheap, reliable electricity on demand, the NEG would not figure among the policy options.

But the challenges of the government are many, including paying heed to the ill-judged commitment to the Paris climate agreement and the need to get states on board. An endorsement from Labor also would be helpful in providing confidence for investors, in the renewable and synchronous energy space.

Of course, the NEG still sticks in my craw. After all, when did central planning ever work? Has Malcolm Turnbull decided those experts in Gosplan, the Soviet Union’s state planning committee, and five-year plans were actually incredibly clever and we should be importing their ideas?

To be fair, electricity may be a special case. It is an essential service and there was always planning at the state level in years gone by, although it was undertaken chiefly by engineers rather than by people who think they know something about economics and business with nary any attention paid to the physics of the system.

You may say the only worthwhile part of the NEG is the reliability component — the requirement that retailers offset their purchase of intermittent energy with solid synchronous sources. By all means, purchase wind power, but the retailers will need to make sure there is available backup to deal with its intermittent nature.

Mind you, it’s important that this requirement is not fiddled by the retailers, which always would be a temptation. The detail will be particularly important.

So why bother with the emissions reduction part? Why would we not rely on market forces to achieve this outcome by believing the renewable energy sector that it will be able to out-compete all other sources of electricity generation? The answer is twofold. First, we should not necessarily believe the claims of the renewable energy sector. There is a high fudge factor in the assertion, including the failure to account for additional costs of transmission and distribution; the uncertain lifetime of some of the installations; and their actual load factors (the energy delivered as a percentage of their nominal capacity).

The second issue relates to what may be termed carbon uncertainty. In the absence of the government having a specific intervention to drive down emissions from the electricity sector, businesses will factor in a shadow price of carbon.

The expectation is a Labor government, with its pledge to double our Paris commitment and to have 50 per cent renewables by 2030, inevitably will introduce a form of carbon pricing, notwithstanding that such action has been political poison in the past. (Note that, in any case, the renewable energy target is a form of carbon pricing, at present sitting at about $80 a megawatt tonne.)

Banks and financiers also will be including carbon risk in their calculations, in turn affecting their willingness to provide finance for new electricity projects. Long-living coal-fired plants, even ultracritical ones with low-emissions intensity, will struggle to get up unless the funders can see a clear path into the future in terms of the handling of emissions reductions.

(A new high-efficiency, low-emissions coal-fired plant also will likely require government guarantees, but that’s fine. It’s what the renewable energy sector is being given by state governments with their expensive reverse auctions funded by taxpayers.)

One of the upsides of the emissions reduction component of the NEG is that the price impact of high penetrations of renewable energy in particular states — for example, South Australia — will be sheeted home directly to consumers. Vote for a government that promotes high renewable energy penetration and pay the price. Not only is this fair but it is sending an efficient price signal in terms of the consequences of particular government policy stances.

That retailers will be able to meet the emissions reduction obligations by purchasing local or international carbon credits (rather than sourcing high-cost renewable energy) is probably the best economic feature of the NEG. With the price of international carbon credits so low at the moment — a few euros per tonne of carbon dioxide — this will be the way to go for many retailers. The option of buying credits should cap the cost of domestic abatement via the purchase of renewable energy.

Don’t forget climate change is a global issue and it doesn’t matter the source or location of the emissions reduction. Note also the government’s own Climate Change Authority has recommended this action as part of least-cost policy.

To be sure, there are some important issues raised by the parallel operation of a reliability obligation and the requirement to meet emissions standards on the part of retailers. Arguably, the gentailers — companies that operate in both the generation and retail space (think AGL, Origin, EnergyAustralia) — will have a serious competitive advantage under the NEG, particularly in terms of accessing hedged contracts.

The worst case scenario would be the withdrawal from the market of some retailers, reducing the limited competition in this space. The option of forcing the gentailers to break up should be considered by the government.

Is the NEG just a form of carbon price in disguise? Is it really true that there will be no further subsidies for renewable energy?

For anyone who understands economics, whenever a constraint is imposed on an activity, an explicit or implicit price emerges. As noted, the RET throws off a carbon price of $80 a tonne of CO2, which is excessive by any standard. And recall that Labor’s carbon price started off at a tad over $23 a tonne. The way to judge the NEG is to ask the question: is the cost of abatement under the NEG lower than the adoption of the Finkel clean energy target? The answer is a clear yes. But this doesn’t mean there will be no further subsidisation of renewable energy. That’s what the emissions reduction guarantee does. It’s just that the degree of subsidisation will be considerably less than it is now, which again is a good outcome.

So should we believe that electricity bills will be $115 a year lower under the NEG? The short answer is that there can be no definitive prediction of this outcome. The Finkel proposition that bills would be lower by $90 a year clearly was manipulated and had no credibility. The $115-a-year figure is more simply derived: it is just the price response you would expect from getting more supply, particularly of reliable energy. The one missing piece of the jigsaw that the government should consider is the scope to change the bidding rules under the National Electricity Market. Under the existing arrangement, the highest bidder sets the price, which is paid to all the intra-marginal suppliers. The aim is to create an incentive to invest.

But it is clear the arrangement has failed to spur investment in reliable electricity while the RET has overwhelmingly driven investment in renewable energy.

The alternative is simply to pay all the bidders needed to meet market demand the actual price they bid. If this were to happen, then there would be significant scope for wholesale prices to fall.

To be sure, the renewable energy sector would complain. And the regulator would need to watch for strategic bidding. But this simple rule change offers the government the best chance to do something quickly rather than wait until after 2020. If I were them, I would be giving this option serious consideration.

The Australian

Judith has got a very clear handle on what the NEG doesn’t do. It does not remove the Large-Scale RET and the retailers’ obligation to purchase 33,000 GWh from eligible renewable energy generators, each and every year between 2020 and 2031 – the target is 26,000 GWh this year and increases over the next 2 years. The cost of that job and industry killer to retail power consumers will still add up to $42 billion between now and then: Sheik-Down, Down-Under: Saudi Billionaire Pockets $300m in Renewable Subsidies

However, the NEG makes it even more unlikely that the ultimate LRET target will ever be satisfied, at least not from wind power generation. In that case, retailers will be simply paying the penalty under the LRET – referred to as the ‘shortfall charge’ – a $65 fine for every MWh that a retailer falls short of the mandated LRET. That penalty will cost retail customers $93, because it is not a tax-deductible expense for retailers.

For reasons set out below, retailers may well opt to pay the shortfall charge, instead of contracting to purchase wind power, leaving power consumers liable to pay what will end up being a $1 billion a year Federal tax on electricity consumers.

Now to the workings of the NEG.

No more blackouts

If the NEG were to be defined by its objective, it would be referred to as a guarantee of ‘No More Blackouts’.

The starting point is a ‘worst case’ demand scenario, using forecast electricity consumption, based on past data. The forecast is to take into account seasonal variations in power demand, related to temperature and weather conditions, from which daily demand can be predicted. At the height of summer, a week of +40°C temperatures across a State heralds maximum demand, as businesses and householders crank up their air-conditioners and refrigerators have to work overtime.

For example, a state like South Australia, on such a day, requires around 3,000 MW to keep the grid up and running.

Up to now, there has been no requirement on retailers to ensure that they have 3,000 MW guaranteed available for delivery. Instead, in South Australia retailers signed up to long-term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with wind power outfits, guaranteeing the purchase of however much wind power is generated from its total capacity of 1,698 MW. (In order to keep the grid stable, AEMO has capped daily wind power output at 1,200 MW, placing a curb on around 500 MW of its capacity, when wind conditions would otherwise see close to 1,600 MW being generated. That move occurred in response to the 28 September 2016 State-wide blackout, when every wind turbine in SA shut down automatically to prevent their self-destruction during a gale, and the system went ‘black’.)

Plenty of experience of sweltering without power has taught South Australians that, on a hot summer day, wind power is usually delivering nothing much at all. A 1,000 MW collapse in wind power output on 8 February this year, when temperatures hit 42°C and wind power output hit the floor, left 90,000 South Australian households boiling in the dark.

Such an event becomes highly unlikely under the NEG.

The NEG is designed as a state-based requirement on retailers that, on such a day in SA, will require them to have contracts with generators securing 3,000 MW of dispatchable power. Dispatchable means coal, gas and hydro. All three sources are delivered to South Australia via two interconnectors (Heywood and Murray Link), with a notional combined capacity of around 870 MW. SA has a 1,280 MW gas-steam plant owned by AGL at Torrens Island and a 440 MW Combined Cycle Gas Turbine plant at Pelican Point, owned by Engie (aka GDF Suez). It has a run of OCGT and diesel peaking plants, with another 276 MW of diesel fueled OCGTs on their way.

Retailers will need to pick from that selection to meet their NEG obligation. At this point many commentators start talking about mega-batteries but, for now, the grid-scale bulk storage of electricity is in the unicorn and pixie dust realm.

Retailer’s NEG obligations are going to be determined on a daily basis by the amount of power they would need to sell to meet their retail customers’ demands, on a worst-case scenario basis: on a scorching SA summer’s day, across all retailers, they will be obliged to have contracted a total of 3,000 MW of dispatchable power. On that scenario, a retailer with a one-third share of the SA market, will need to have contracted to secure 1,000 MW of dispatchable power to meet their NEG obligation.

In other words, for every MW a retailer has promised to sell its customers, it will need to have a contract to purchase a MW of dispatchable power to meet that promise.

In markets where a commodity is sold forward by its producer to a trader (fixing a price long before it is ready for delivery), the trader covers that purchase with another contract to sell the commodity to a processor or end user at the nominated time for delivery, so that the two contracts operate ‘back-to-back’, and the risk is spread across both. The NEG will result in the same type of market for dispatchable power. In effect, retailers have already promised (and therefore forward sold) power to their retail customers. Under the NEG they will be bound to contract with generators of dispatchable power for the same volume they should expect to deliver to their customers on a worst-case scenario, on any given day.

A very big stick

STT’s Canberra operatives tell us that the precise form of the penalties to be applied to retailers who fail to satisfy their NEG obligations is yet to be determined. However, we are reliably informed that it will be a very big stick, indeed.

One option is to penalise retailers to the extent they have failed to contract to meet their NEG obligation, by making them liable for the costs incurred by the grid manager in obtaining supply from dispatchable sources. On a worst-case scenario, that will add up to serious money, as peaking power generators can charge the grid manager prices all the way to the market cap of $14,000 per MWh.

However, we hear that the most likely scheme will involve a sliding scale of penalties, starting with Civil Penalty Units, with a defined value (as is the case under all sorts of Commonwealth Legislation, where civil penalties are enforced).

The number of Penalty Units applied in each case of a breach will relate to the number of MWhs that the retailer failed to contract to meet their NEG obligation on the day. STT is told that the financial penalties are going to be very severe.

Repeated or flagrant breaches by a retailer of their NEG obligation will result in their suspension from the market, until the default has been remedied. A refusal or failure to remedy after a notice of default has been served, may also result in de-registration and the de-listing of the retailer, preventing them from participating in the market, altogether.

The end for worthless wind power

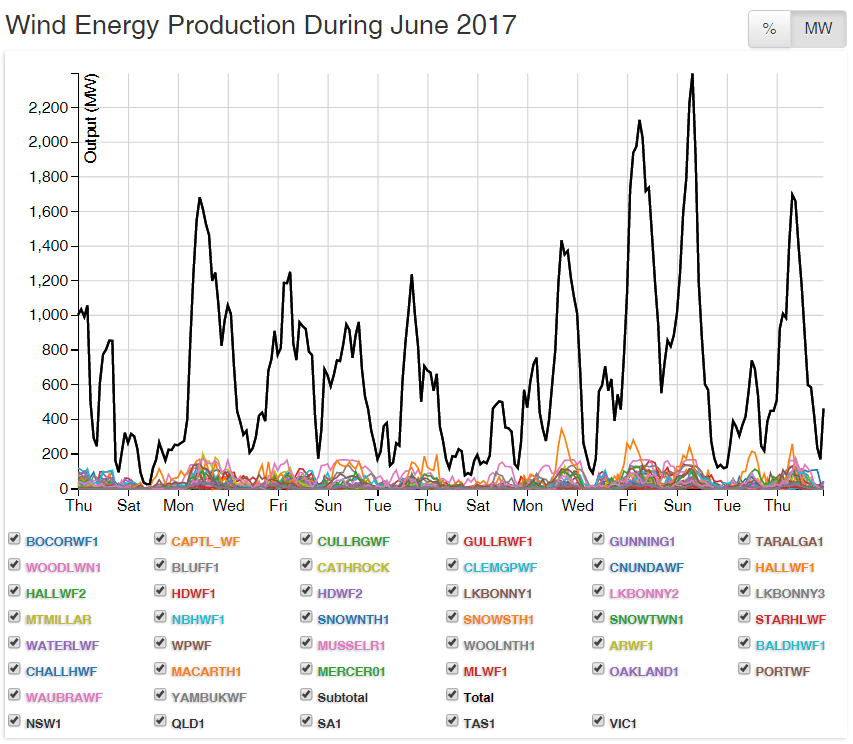

A retailer will not satisfy its NEG obligation by contracting to purchase wind power, principally because, on a worst-case scenario, wind power is simply incapable of being reliably delivered.

As noted above, hot weather coincides with calm weather and, therefore, no wind power. However, wild winter storms, with wind speeds in excess of 90 km/h cause wind turbines to automatically shutdown – with the same result: no wind power at all. And often, in the depth of winter there is bitterly cold, frosty weather across south-eastern Australia. Those occasions also coincide with no wind and, therefore, no wind power (see above the entire output of every wind turbine connected to the Eastern Grid in June this year). In short, in terms of satisfying the NEG obligation, wind power is absolutely worthless.

Solar, however, tends to operate in stinking hot weather, rather well. During summer, solar power continues to be delivered until well into the late afternoon, with the output curve dropping sharply after about 6pm (in those states with daylight saving). On a worst-case scenario, a retailer is highly likely to contract to purchase solar power, because it is highly likely to be available, for most of the day; matching more closely the demand curve for power during hot weather. This tends to suggest that there will be a surge in the construction of new large-scale solar plants, aimed at satisfying both the NEG and the Emissions Obligation (which we deal with below).

Retailers may well look to householders with rooftop solar as potential suppliers to contract with and meet their NEG obligations, as well as contracting with large-scale solar generators. While solar shuts down at night-time, it is still much more predictable than wind power. Hence, it is going to have some value for retailers setting out to satisfy their NEG obligations.

The NEG spells doom for wind power, because it applies across the entire State’s market and includes existing wind power generation. For South Australia, as we detailed above, it means that for every one of its 1,698 MW of wind power capacity – currently contracted under PPA’s with retailers at around $110 per MWh – those retailers will need to find a MW of dispatchable power somewhere in the system, and to contract with the generators of that power to avoid the penalties to be applied under the NEG. In SA, that means retailers will be bound to contract to secure 1,698 MW of coal, gas or hydro (delivered via the interconnectors in the case of coal and hydro). That result follows from the fact that SA’s 18 wind farms are guaranteed not to deliver power when it is needed most.

With the NEG in place, no retailer in their right mind is going to enter a PPA to purchase any more wind power, simply because for every MW of wind they contract to purchase, under the NEG, they will be obliged to contract to secure another MW of power generated by coal, gas or hydro.

STT predicts that there will be no new wind farms built in Australia.

The penalties for failing to meet the NEG will be so severe, that retailers will refuse to sign up to purchase any more wind power in long-term PPAs. Instead, retailers will gladly pay the $65 per MWh shortfall penalty – that applies to their failure to satisfy the target set by the LRET – a penalty which will seem like peanuts, compared to the consequences of a failure to satisfy their NEG obligations.

The Emissions Obligation

Yes, carbon dioxide gas is plant food and, even if it is about to cause the incineration of the Planet, the minuscule amount produced by Australia is like a zephyr in a thimble compared to the CO2 being pumped out of hundreds of coal-fired power plants in places like India and China. However, for as long as Malcolm Turnbull leads the Liberal/National Coalition, CO2 gas will be treated as ‘pollution’.

The Emissions Obligation differs from the NEG in that the Emissions Obligation operates nationally, whereas the NEG operates at a State market level.

As a result, retailers accounting for their Emissions Obligation will be able to secure low emissions electricity from anywhere in Australia, and from a whole variety of sources, not just wind and solar.

The Obligation will start at 650 kg of CO2 per MWh. And that figure will be applied as an average across all of the power delivered by a retailer. Retailers are likely to scramble to contract and secure every last watt of hydro power, from the moment trading begins under the NEG system, simply because it will satisfy both their NEG obligation and their Emissions Obligation.

Gas-fired power (when used in efficient Combined Cycle Gas Turbine or gas-steam plant, like AGL’s Torrens Island plant in SA) will comfortably satisfy the Emissions Obligation, as well as the NEG obligation. CCGTs average between 400 and 650 kg of CO2 per MWh dispatched. The average for CCGTs in Australia is closer to 400 kg per MWh: 20140411_Emissions_report_V2

The only thing against gas-fired power in recent years has been the rising price of gas and an illiquid spot market. Gas suppliers have preferred secure, long-term contracts with overseas customers, like South Korea, China and Japan, over supplying gas for a few hours a day to OCGT peaking plants, which dispatch power only when the sun goes down and/or the wind stops blowing.

However, if gas-fired generators are able to secure long-term NEG contracts with retailers, those gas-fired generators should, in turn, be able to secure long-term contracts with gas suppliers, at reasonable prices.

There has been plenty of talk about High Efficiency Low Emissions coal-fired plant, which would help retailers satisfy the Emissions Obligation, as well as the NEG. HELE plant are capable of generating power with CO2 emissions in the order of 670 to 740 kg per MWh dispatched: HELE – part_of_Australia’s_energy_solution

The NEG has been designed to provide a long-term secure investment environment that would encourage private investment to build HELE plant.

STT’s NSW operatives tell us that just such a plant is being scoped out in the Hunter Valley, simply because the NEG now makes coal-fired power an extremely valuable commodity.

As HELE plant obviously satisfies the NEG obligation and would help retailers satisfy their Emissions Obligation as well, STT suggests that the chances of a number of such plants being built have greatly improved. Having retailers eager to sign up to secure reliable, low emissions power from a new HELE plant is what improves those chances. But getting them built may require some additional guarantees from the Federal government, or perhaps co-investment with a state government.

Because the NEG obligation now places a premium on reliability, old coal-fired power plant will cease being treated like diseased lepers, and will now be fêted like the prodigal son.

AGL, for example, has been talking up the closure of its 2,000 MW Liddell coal-fired plant in NSW for the last few months. When the NEG was announced, AGL was asked about its plans for Liddell in its wake. AGL refused to comment, principally because under the NEG, AGL will need every last MW of coal-fired power it can lay its hands-on. STT expects the Liddell plant to be chugging away for decades to come. Oh, and AGL won’t be “getting out of coal” any time soon; it can’t afford to.

The Emissions Obligation will require old coal-fired plant to clean up their act, principally by investing in more efficient fire-boxes and boilers. Not only does the NEG create a market for new HELE plant, efforts to extract CO2 from the exhaust gases of coal-fired plant would be encouraged. Perhaps not ‘Carbon’ Capture as previously envisaged, but some system that would enable coal-fired generators to meet the 650 kg per MWh requirement.

As Judith Sloan points out, retailers will be able to meet the Emissions Obligation by purchasing international carbon credits, currently worth around $8-10, or the local equivalent, the Australian Carbon Credit Unit. ACCUs are issued to so-called ‘carbon farmers’, capturing CO2 by planting trees and restoring vegetation to denuded pastoral range-lands. Power retailers will now be able to purchase ACCUs from carbon farmers and anyone else who holds them in order to meet their Emissions Obligation, without purchasing wind power.

As we said above – because it’s generally available in the worst-case scenario (extreme temperatures, leading to peak demand for power, no wind and, therefore, no wind power to supply that demand) – solar power is going to find a ready market with retailers, including what’s being generated on hundreds of thousands of suburban rooftops. Retailers will use the solar power they secure to partially satisfy their NEG obligations on worst-case scenario Summer’s days, to satisfy their Emissions Obligation as well, with every MWh purchased being counted as CO2 free.

Nuclear Power is now firmly on the table

Australia is the only G20 country with a legislated prohibition on nuclear power generation.

However, the combination of the NEG and the Emissions Obligation puts nuclear power firmly on the table. As we have said repeatedly, nuclear power is the only stand-alone power generation source which is capable of delivering power on demand, without CO2 emissions being generated in the process.

From a retailer’s perspective, nuclear power is a source which is obviously capable of satisfying both its NEG obligation and its Emissions Obligations, were such a choice available.

When Alan Finkel put together his unicorns and pixie dust review of Australia’s renewable energy debacle, he managed to dismiss nuclear power in two short paragraphs.

Now that reliability is the primary focus of energy policy under the NEG, sources with a 100% capability of delivering power, irrespective of the time of day or the weather, will necessarily attract attention. Add in an obligation (along with sufficient penalties) to deliver that power without CO2 emissions being generated, and the case for nuclear power in Australia becomes obvious and compelling.

The French use nuclear power to generate around 75% of their electricity and the French pay fully half what it costs retail customers in South Australia. So, those who claim nuclear power is expensive, clearly haven’t been paying attention.

STT will continue to advocate for nuclear power. The NEG and Emissions Obligation guarantee that nuclear power will generate plenty of discussion, debate and interest, from here on.

The RET still has to go

STT’s analysis is based on our well-informed Canberra sources, who are as hostile to renewable subsidies as we are. What we have attempted to do above is to detail what the NEG and the associated Emissions Obligation are designed to do; what they will mean in terms of re-stabilising Australia’s power grid; and what happens to the Australian wind industry, from here.

As Judith Sloan points out, the NEG has some merit, but plenty that tells against it.

It is, after all, a government intervention to counteract the consequences of earlier government intervention. Like a rabid dog chasing its tail, or placing more and more Band-Aids on top of bloody Band-Aids.

In the short term, STT does not see any relief for power consumers under the NEG, other than preventing mass load-shedding events and state-wide blackouts; which are not insignificant occasions for those who have suffered them – ask a South Australian.

The NEG will secure the continued operation of existing reliable power generation sources into the future; and, over the longer term, encourage the construction of new generators capable of dispatching power on demand.

It will also encourage the owners of existing coal-fired generators to re-fit and refurbish their plant, with the object of improving their efficiency and lowering CO2 emissions. It will also mean that any new generation capacity will be as efficient as engineering and physics allows. For now, that means HELE coal-fired power plant, in future it means nuclear power, too.

The NEG will satisfy the essential requirements that electricity supplies be reliable and secure. Whether Australia’s electricity will be affordable in the future is an open question.

For that reason, STT will continue to attack the principal cause of all of this chaos: the Federal government’s Large-Scale Renewable Energy Target.

While Malcolm Turnbull is PM, the LRET will remain. If Bill Shorten takes the top spot in a Labor/Green alliance, then lunatics from the left will push to increase the LRET, even further.

The LRET is a $60 billion tax on all Australian power consumers, the largest single industry subsidy scheme in the history of the Commonwealth and the greatest wealth transfer of all time. It doesn’t, as some commentators seem to think, end in 2020. That’s when the LRET hits its ultimate 33,000 GWh target: if that target is met, wind and large-scale solar generators will receive 33 million Renewable Energy Certificates each and every year from 2020 until 2031. Those certificates are currently worth $85 and are designed to trade at $93. However, if our analysis is correct, retail power consumers will be paying the shortfall penalty, to the tune of hundreds of $millions every year, because the ultimate LRET target will not be satisfied.

What the NEG might do for Australian power consumers is a matter conjecture, and will be for some time.

What the LRET has already done is, without doubt, a self-inflicted policy calamity, the consequences of which Australian households and businesses are forced to suffer every day. The NEG is designed to salvage Australia’s power grid from the inevitable consequences of the LRET. Putting the NEG, combined with an Emissions Obligation, in place while the LRET remains in operation makes absolutely no sense at all.

The LRET is an economic disaster and simply must go now. This Country’s economic future depends upon killing it off and starting anew. The NEG offers the perfect opportunity to axe the LRET, once and for all. Over to you Malcolm.

I’m not sure what’s more difficult to comprehend, the complexities of our weather systems and the arguments to whether man has induced climate change or understanding the PM’s energy plan and its ramifications.

Up here in the mid north of SA at Hallett, we are wind central, the utopia of the wind industry, there are more turbines than residents A product of Mike Rann’s economic and environmental salvation in the early 2000’s. For those of us left, they are talked about in hushed tones these days, their presence has divided this once united community.

Has the environment or Australia prospered from there infiltration in our community?

What have we learned?

They are heavily subsidised by the Australian power consumer and only work when they want to.

I now hear when the wind is blowing too hard AEMO has to cut back on wind energy and fire up gas generators to keep the system stable.

I also hear the great minds want to subsidise the non use of power during times of peak power.

I look out my window and wonder who will pull these monstrosities down at the end of their working life and then what power source will replace them.

Will there be any justice for the local community and the Australian people for those who brought this scourge upon us?

Will there ever be a Royal Commission?

The answer is blowing in the wind.

Following is an example of energy requirements and production, just to illustrate that we are paying a VERY high price both financially and socially for so called Renewables to completely take over the way our price structure of energy supply is created, even though they are such a very small part of its production.

It also shows how insecure reliance on wind is and how we should NEVER rely on it being available at any time.

We are not even into the high summer demands and wind production is failing. At time in the past week NSW has been producing as little as 1MW of wind energy and maybe even nothing at times.

For anyone to even think we will ever be able to rely on wind energy to provide our needs is evidence of madness. Even the use of batteries will never be able to store sufficient supply to keep the lights on when the wind doesn’t blow for even for a few hours. I can’t see how the NEG or anything other than stopping the installation of Wind, and the support of clean coal or even Nuclear can prevent a massive blackout across the grid in the future – until then we live on a knifes edge.

At 8.19am SA time AEMO Dashboard-

ENERGY DEMAND MW’s

SA 1,249

VIC 5,492

NSW 7,756

TAS 1,214

QLD 6,083

Wind and other MW’s

SA 191 Installed capacity 1,679

VIC 447 1,425

NSW 25 651

TAS 99 308

QLD – Nil

At 8.11am SA time-

Wind taken from http://anero.id/energy/wind-energy:

SA 144

VIC 12

NSW 6

TAS 48

Who nobbled the Lovely Audrey?

A picture paints a thousand words. As the PM delivered his new energy policy surrounded by other members of the Energy Security Council I couldn’t help notice at the end of the bench sat the AEMO’s Lovely Audrey.

Looking like she’d been sucking on a lemon for the last half hour, my bet is she will be back in the Big Apple within a year.

For months she has been preaching to the converted that it was time to take the emotion out of the energy debate and get on with the transition. I’m not sure who pulled rank on her but I think she will find it hard towing the line. I see a new chairman of AEMO has been appointed in Drew Clark, perhaps he’s been sent into wield the whip.

Hallelujah to putting the brakes on the wind industry.

As for lowering prices, pull the other one!

Meshing together RET with certainty of dispatch able supply is double dipping and no prizes for guessing who will end up paying for that.

.

This is about keeping the grid from collapsing, first and foremost.

Could we not all agree that, to avoid continuing deception, we all refer to “carbon dioxide” rather than “carbon”? This is not an accidental abbreviation, but a deliberate ploy to make the gas seem dirty and objectionable, when we all know it is a clear life-supporting gas. I can understand the warmists wanting to perpetuate this lie, but surely we proud skeptics should know better!

STT agrees. We use the long form, carbon dioxide gas or CO2. But we can’t control what MSM journalists write and we reproduce their pieces, in full.

Almost certainly the latest Turnbull/Frydenberg thought bubble will turn out to be a shambles.

For instance, what is the time period and physical domain within which a retailer must buy at least 1MW of baseload for 1MW of intermittent?

Currently the ratio is greater than 3:1 over a year and in 2030 would be 1.5:1 even under Finkel’s CET, or 2:1 without it. So unless the reconciliation period is very short, the requirement imposes no real constraint nationally, though conceivably it might if applied on a state by state basis.

That brings the next point. Retail is now dominated by a three party oligopoly, whose members generate and sell in all states in the NEM. If AGL says power from its Hallett wind farms is for its customers in NSW, being comingled with electrons from Liddell, and no doubt they can arrange their internal accounting to prove it, how does Turnberg think they can demonstrate otherwise?

A large volume of power is bought spot from the grid. There is no marker on the electrons from wind, solar, coal, gas etc and AEMO doesn’t distribute it as such. So how does Frybull plan to determine how much each retailer bought from which source?

This latest nonsense from Frybull is just spin, with no actual concern about providing reliable and affordable power to

Australia. If that was their aim they would simply adopt the policies previously advocated at STT and they would happily go to an election with that clear plan to return Australia to cheap and reliable power.

Instead they have a cockamamie yarn they think they can put over a gullible public, while doing not a thing to achieve cheap and reliable electricity.

Michael, our understanding is that the NEG obligations will require the retailer to be covered to the required level, each and every day. The forecast demand for the day in question will determine the volume of dispatchable power that the retailer will need to have contracted in advance. The lead times will be days, not months.

But otherwise agree with your comment. How much simpler it would be to cap the RET at the current volume, sunset clause the rest and rework the NEM bidding rules to prevent the highest marginal bid setting the dispatch price. Although we hear that the bidding rules are under scrutiny.

I agree Michael – add to that that Frydenberg has said today that there will be 28-32% renewables by 2030 – the mind boggles! That’s more than double the figure for Australia today, which includes ‘old hydro’.

STT’s and Judith Sloan’s attempt at deciphering Turnbull and Frydenberg’s new policy is most admirable and may well be correct – but to me at this stage, it remains an absolute dog’s breakfast with even more government intervention by even more government agencies who have great capacity for following their own agenda regardless of government intention (eg Chloe Monroe of Clean Energy Regulator fame). As STT says, one thing is clear, the cause of the entire mess is still burning brightly, the LRET and LREC system – so brightly in fact I would be grateful if someone could explain why this will not mean that in the next two years AGL, and perhaps the other gentailers, will go hell for leather building as many wind farms, as well as solar farms, plus ocgt’s as quick fix back up, to capitalise on both their renewables obligations and their baseload (NEG) obligations using the subsidy money handed out in LREC’s . This was always AGL’s plan and it occurs to me that the million dollar men, Turnbull and Vesey, have sorted this part between them with zero regard for pricing and zero regard for the Australian people. Nothing, it seems to me, will change until our politicians put an immediate stop to the RET and REC system – if Turnbull and Frydenberg won’t do it then they must go.

Factual errors:

Liddell was a 2000 power station, recently downgraded to 2400MW. Not 2200MW.

CCGT carbon intensity is far lower that the quoted 600+ g/kWh. There are many online sources for this type of information. In the Australian context, this one from AEMO includes historical data from a large number of generators.

Click to access 20140411_Emissions_report_V2.pdf

We have corrected the figure for Liddell, thanks for pointing that out.

You are also right about modern CCGTs and their emissions, that is why we gave a range from 400 kg per MWh (relating to the most efficient modern plant) to 650 kg per MWh (for older units). In putting forward those figures we had regard to the AEMO document you attempted to link. We have now included it in the post.