In a world-first, neighbours tormented by wind turbine noise have won a landmark victory, forcing the operator to shut down all of its turbines at night-time.

Yesterday, Justice Melinda Richards of the Victorian Supreme Court slapped an injunction on a wind farm because the noise it generates has been driving neighbours nuts for seven years, and the operator has done absolutely nothing about their suffering.

Her Honour also ordered damages, including aggravated damages for the high-handed way in which the operator has treated its victims. Since March 2015, the community surrounding the Bald Hills wind farm have been tortured by low-frequency noise and infrasound generated by 52, 2 MW Senvion MM92s.

Neighbours started complaining to the operator about noise, straightaway. But, as is their wont, the operator simply rejected the mounting complaints and carried on regardless.

Locals, however, were not perturbed. Instead, they lawyered up. Engaging the tough and tenacious Dominica Tannock.

Starting in April 2016, Dominica went after the South Gippsland Shire Council which, under the Victorian Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 has responsibility for investigating nuisance complaints and a statutory obligation to remedy all such complaints within its municipal district.

The locals won that round, when Justice Richards found the wind turbine noise generated constituted an ‘unreasonable nuisance’ as defined by the Public Health and Wellbeing Act.

Following that victory, Dominica launched civil proceedings in the Supreme Court, based on an action in common law nuisance. There were 13 plaintiffs in all – when the action started there were 6 plaintiffs, who were later joined by another 7.

Over time, Dominica was able to settle the claims of 11 of her clients on very favourable (confidential) terms – STT hears that those who settled pocketed figures of more than $2m for each affected household.

However, two of the plaintiffs, Noel Uren and John Zakula rejected the operator’s monetary overtures, because they were furious with the way that the neighbours have been treated and, accordingly, determined to take the matter all the way.

After a bruising piece of litigation (where the operator withheld critical evidence from the plaintiffs and its acoustic consultant was caught out ‘filtering’ – ie destroying – rafts of noise data) and a hard-fought trial, these thoroughly courageous gentlemen have established what has been known, all along: everyone has a legally enforceable right to sleep soundly at night in their very own homes; and the wind industry has been destroying that right with impunity, for far too long.

What Noel Uren and John Zakula have achieved is not just notable and noble, it reflects the adage about evil prevailing when good men do nothing.

Refusing to be cowered by the operator’s threats, bullying and intimidation, these men did something and, accordingly, every wind industry victim owes them a debt of eternal gratitude for what they have achieved and placed on the public record. At last. At long last. Vindication. Sweet vindication.

What their efforts have also brought to the surface, is the monstrous corruption that is part and parcel of the wind industry, which has compromised the integrity of every political and government institution in this Country, and anywhere in the world it operates.

At one point during the trial, the National Wind Farm Commissioner (a Federally appointed wind industry stooge) approached the judge’s Chambers directly, without the knowledge of the plaintiffs’ lawyers, and offered his “assistance” to Justice Richards, including an offer to provide her with knowledge and information about how ‘wonderful’ wind turbines really are. Justice Richards was not amused.

The judgment is the first of its kind, where plaintiffs have established that the noise generated from wind turbines constitutes an unreasonable interference with the use and enjoyment of their homes and, therefore, an actionable nuisance, at common law.

The decision is, therefore, of immeasurable significance to any of the wind industry’s victims, anywhere in the common law world; Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the UK, for starters. And, no doubt, it will be seized on by our American cousins in the US.

The full judgment appears here: Uren v Bald Hills WF [2022] VSC 145

At 148 pages it is a thumping analysis of the evidence and issues, and well worth careful consideration. However, set out below are the key extracts of Justice Richard’s reasons, interposed with our commentary on the factual background and legal principles in issue, appearing in square brackets. Note that the extracts below do not contain the citations to the legal authorities or evidence. For that, you need to see the PDF of the judgment linked above. Please enjoy and share widely the judgment in Uren & Zakula v Bald Hills Wind Farm Pty Ltd [2022] VSC 145

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF VICTORIA

AT MELBOURNE

COMMON LAW DIVISION

MAJOR TORTS LIST

S ECI 2020 00471

NOEL UREN and JOHN ZAKULA

Plaintiffs

v

BALD HILLS WIND FARM PTY LTD

Defendant

JUDGE: Richards J

WHERE HELD: Melbourne

DATE OF HEARING: 6–10, 13–17, 20–23 September, 12 October 2021

DATE OF JUDGMENT: 25 March 2022

CASE MAY BE CITED AS: Uren v Bald Hills Wind Farm Pty Ltd

MEDIUM NEUTRAL CITATION: [2022] VSC 145

….

OVERVIEW

The Bald Hills wind farm is located near Tarwin Lower in South Gippsland, Victoria. Since it began operating in 2015, the wind farm has received many complaints from neighbouring residents and landowners about noise from the wind turbines. In this proceeding, two of those neighbours, Noel Uren and John Zakula, seek remedies from the operator of the wind farm, Bald Hills Wind Farm Pty Ltd, for common law nuisance.

From about 1994, Mr Uren lived in a house at 1550 Buffalo-Waratah Road, Tarwin Lower on land that he owned together with his brother, Bruce Uren. The Uren brothers farmed sheep and cattle on that land, and on another property to the north at 87 Kings Flat Road, Tarwin Lower, together the Uren properties. Their partnership dissolved in mid-2015 and the Uren properties were sold. The southern property, on which Mr Uren was living, sold on 18 March 2016. By agreement with the new owner, Mr Uren continued living in the house until December 2018, when he moved into the town of Tarwin Lower.

Mr Zakula bought his property at 860 Buffalo-Waratah Road, Tarwin Lower in June 2008. He described the land that he bought as a ‘cow paddock’, on which he planned to establish an organic farm. Mr Zakula established windbreaks of native vegetation around the property, and planted olive, fruit and nut trees. While there was no house on the property when he bought it, there was a planning permit to build a dwelling. Mr Zakula designed and built an energy efficient house on the property, which was completed during 2011. He moved into the house in late 2011 and has lived there since.

…

The Minister granted planning permit TRA/03/002 on 19 August 2004, which allowed the use and development of land ‘for a wind energy facility for the generation and transmission of electricity from wind generators, together with associated buildings and works’. The permit allowed the construction of a wind farm of 52 turbines of up to 110 metres each, and included detailed conditions concerning acoustic amenity. The permit prescribed noise conditions, which applied the noise limits and methodology set out in the New Zealand Standard 6808:1998 – Acoustics – The Assessment and Measurement of Sound from Wind Turbine Generators (NZ Standard).

Construction of the wind farm commenced in about 2012 and was completed during 2015. The first of the 52 turbines started generating electricity in February 2015, and the wind farm was fully operational by September 2015

In February 2020, Mr Uren, Mr Zakula and ten of their neighbours commenced this proceeding. The other plaintiffs resolved their claims against Bald Hills before the trial of the proceeding, and were removed as parties. Six of the former plaintiffs — Don and Dorothy Fairbrother, Don and Sally Jelbart, Stuart Kilsby and Alexander McDougall — were called as witnesses by Mr Uren and Mr Zakula.

The issues for determination in the proceeding, and my conclusions in relation to each issue, are as follows.

Nuisance

(1) Has noise from wind turbines on the wind farm operated by Bald Hills caused a substantial interference with the plaintiffs’ use and enjoyment of their land?

Yes. Noise from the turbines on the wind farm has caused a substantial interference with both plaintiffs’ enjoyment of their land — specifically, their ability to sleep undisturbed at night, in their own beds in their own homes. The interference has been intermittent and, in Mr Zakula’s case, is ongoing. While both Mr Uren and Mr Zakula have been annoyed by the sound of the turbines during the day, it has not substantially interfered with their enjoyment of their properties.

(2) If yes to question 1, does the burden shift to Bald Hills to establish that the interference was reasonable?

It is unnecessary to decide this question, because the evidence enables me to make the necessary findings of fact in relation to most issues. Bald Hills accepted that it bore the burden of proof on the one issue on which I may have been left in doubt, which is whether the sound from the turbines received on the plaintiffs’ land at all times complied with the noise conditions in the permit.

(3) What is the nature and extent of the interference?

The interference does not involve property damage or personal injury. It is an interference with the acoustic amenity of the plaintiffs’ properties, in particular their ability to sleep undisturbed in their beds at night. The interference is substantial, albeit intermittent, and in Mr Zakula’s case is ongoing.

(4) Has the sound from the turbines received on the plaintiffs’ land at all times complied with the noise conditions in the permit?

Bald Hills has not established that the sound received at either Mr Uren’s house or Mr Zakula’s house complied with the noise conditions in the permit at any time. Permit compliance is not determined by the Minister, who is the responsible authority for the permit. While the Minister can initiate enforcement action, it is for the relevant court or tribunal to determine permit compliance.

Bald Hills did not demonstrate compliance with condition 19(a) of the permit, either by the 2021 assessment of noise monitoring data undertaken by its acoustic expert, Christopher Turnbull, or his review of MDA’s noise assessments. Mr Turnbull’s method for assessing compliance with condition 19(a) was not the method prescribed by the NZ Standard, properly interpreted. MDA initially did not assess compliance at Mr Zakula’s house or at Mr Uren’s house, but at other nearby locations. The findings of the noise assessment reports MDA produced for Mr Zakula’s house in March 2017 and for Mr Zakula’s house in June 2017 were plainly flawed.

Neither Mr Turnbull nor MDA demonstrated compliance with condition 19(c), in relation to the night period. Condition 19(c) provides a ‘hard measure’ for protecting sleep and requires assessment on individual nights.

In addition, neither Mr Turnbull nor MDA properly applied condition 19(b) of the permit in assessing compliance with conditions 19(a) and 19(c).

(5) If so, what is the relevance of compliance with the noise limits in the permit?

Demonstrated compliance with the NZ Standard and condition 19 of the permit would not necessarily have established that the noise that from time to time disturbed Mr Uren’s and Mr Zakula’s sleep was reasonable. Significantly, the NZ Standard sets a limit on the extent to which wind turbine noise may increase continuous underlying noise levels, assessed over a long period. It is not directed to intermittent loud noise from wind turbines, and does not provide a way of assessing whether a wind farm produces unreasonably annoying noise in certain weather conditions, or on a particular night.

(6) What is the social and public interest value in operating the turbines to generate renewable energy?

The generation of renewable energy by the wind farm is a socially valuable activity, and it is in the public interest for it to continue. However, there is not a binary choice to be made between the generation of clean energy by the wind farm, and a good night’s sleep for its neighbours. It should be possible to achieve both.

(7) Is either of the plaintiffs hypersensitive to noise from the turbines?

No. Neither Mr Zakula nor Mr Uren is hypersensitive to wind farm noise.

(8) What is the character of and the nature of established uses in the locality of the plaintiffs’ land?

Both properties are in a relatively quiet and remote rural locality. Sounds associated with farming activities are typical of the area during the day, but do not cause intrusive noise at night. Traffic on nearby roads is light and usually creates limited disturbance. The wind farm itself cannot be taken into account as an established use in the locality, because it has not established compliance with the noise conditions in the permit or Div 5, Pt 5.3 of the Environment Protection Regulations 2021 (Vic).

(9) What precautions has Bald Hills taken to avoid or minimise the interference?

Bald Hills has not demonstrated compliance with the noise conditions in the permit at Mr Uren’s house or at Mr Zakula’s house at any time. While Bald Hills investigated and responded to their numerous complaints, it did not take any remedial action to reduce the noise from wind turbines received at either property.

(10) Could Bald Hills reasonably have taken any other precautions?

Bald Hills could reasonably have taken at least two further precautions to reduce the noise levels at the plaintiffs’ homes. It could have implemented selective noise optimisation of nearby turbines. It could also have remedied the gearbox tonality issue that was identified by MDA in December 2016.

(11) Having regard to the answers to questions 3 to 10, has the interference with the plaintiffs’ use and enjoyment of their land been unreasonable?

Yes. Noise from the wind turbines on the wind farm has amounted, intermittently at night, to a substantial and unreasonable interference with the plaintiffs’ enjoyment of their land. The wind farm noise has been a common law nuisance at both properties.

(12) If yes to question 11, will noise from the turbines continue to cause a substantial and unreasonable interference with Mr Zakula’s use and enjoyment of his land?

Yes. The nuisance is ongoing at Mr Zakula’s property.

Injunction

(13) If yes to question 12, should an injunction be granted restraining Bald Hills from continuing the nuisance?

Yes. An injunction to abate the nuisance is the primary remedy sought by Mr Zakula, and an injunction will be granted. I do not consider that damages would be an adequate remedy, or that I should exercise my discretion to award damages instead of an injunction for any other reason.

(14) If so, in what terms?

I will grant an injunction restraining Bald Hills from continuing to permit noise from wind turbines on the wind farm to cause a nuisance at Mr Zakula’s house at night, and requiring it to take necessary measures to abate the nuisance. The injunction will be stayed for three months.

Damages

(15) Is Mr Uren entitled to damages in respect of the alleged decline in value of his share of the Uren properties?

No.

(16) If so, what is the quantum of that loss and damage?

Does not arise.

(17) Is Mr Uren entitled to any remedy in respect of nuisance after 18 March 2016?

Yes. Mr Uren had a leasehold interest in the house on the southern property from March 2016 until December 2018, and he is entitled to damages for nuisance for that period.

(18) If an injunction is not granted to restrain the defendant from continuing the nuisance, is Mr Zakula entitled to any damages in respect of the alleged diminution in value of his land attributable to the nuisance, or the cost of abating the nuisance?

I have decided to grant an injunction requiring Bald Hills to abate the nuisance. Had I not done so, Mr Zakula would have been entitled to damages for the reduction in value of his property attributable to the nuisance.

(19) If so, what is the quantum of that loss and damage?

The noise nuisance from the wind turbines, if it were to continue, would reduce the value of Mr Zakula’s property by $200,000.

(20) Is either plaintiff entitled to damages for distress, inconvenience and annoyance, and if so in what amount?

Yes. Both plaintiffs are entitled to damages for past loss of amenity, in the amount of $12,000 per year, or $1,000 per month. Mr Uren is entitled to damages of $46,000, and Mr Zakula is entitled to damages of $84,000.

(21) Should aggravated damages be awarded to either plaintiff, and if so in what amount?

Yes. Bald Hills’ conduct towards both Mr Uren and Mr Zakula was highhanded and warrants an award of aggravated damages. The manner in which Bald Hills dealt with the plaintiffs’ reasonable and legitimate complaints of noise, over many years, at least doubled the impact of the loss of amenity each of them suffered at their homes. There will be an award of aggravated damages of $46,000 to Mr Uren, and $84,000 to Mr Zakula.

(22) Should exemplary damages be awarded to either plaintiff, and if so in what amount?

No. I do not consider that Bald Hills engaged in conscious wrongdoing or acted in contumelious disregard of the plaintiffs’ right to sleep peacefully in their own homes.

(23) What is the proper measure of each plaintiff’s loss and damage, having regard to the answers to questions 15 to 22 above?

Mr Uren will be awarded damages in the amount of $92,000, comprising $46,000 for past loss of amenity, and $46,000 for aggravated damages. Mr Zakula will be awarded damages of $168,000, comprising $84,000 for past loss of amenity, and $84,000 for aggravated damages.

…

NUISANCE

A person commits a private nuisance if that person interferes with another person’s use or enjoyment of their land in a way that is both substantial and unreasonable. In Hargrave v Goldman, Windeyer J described the basis of liability for nuisance in this way:

In nuisance liability is founded upon a state of affairs, created, adopted or continued by one person (otherwise than in the reasonable and convenient use by him of his own land) which, to a substantial degree, harms another person (an owner or occupier of land) in his enjoyment of his land.

Whether an interference is substantial is a question of fact. A substantial interference may involve property damage, personal injury, or harm to an occupier’s use or enjoyment of land; for example, by air pollution, vibration, noise or dust. While it does not extend to a trivial interference, or protect those of ‘delicate or fastidious’ habits, it does include an interference that disturbs an occupier’s sleep.

Whether an interference is unreasonable is an objective question, to be answered by ‘weighing the respective rights of the parties in the use of their land to make a value judgment as to whether the interference is unreasonable’. The authorities direct attention to a range of considerations that may be relevant to the question of reasonableness. These were summarised by the Court of Appeal of Western Australia in Southern Properties (WA) Pty Ltd v Executive Director of the Department of Conservation and Land Management:

To constitute a nuisance, the interference must be unreasonable. In making that judgment, regard is had to a variety of factors including: the nature and extent of the harm or interference; the social or public interest value in the defendant’s activity; the hypersensitivity (if any) of the user or use of the claimant’s land; the nature of established uses in the locality (eg residential, industrial, rural); whether all reasonable precautions were taken to minimise any interference; and the type of damage suffered.

This formulation has been adopted in a subsequent Court of Appeal decision in Western Australia, and has been applied by single judges of this Court.

…

[Her Honour then consider the evidence given by John Zakula and the evidence given by the wind industry’s ‘go to’ acoustic ‘expert’, Chris Turnbull and held]:

I find that noise from the turbines on the wind farm has woken Mr Zakula or kept him awake on hundreds of occasions since June 2015. There were nights when he was unable to sleep at all. There were others when he left home and slept in his car at Walkerville beach to escape the noise. On any view, this amounts to a substantial interference with Mr Zakula’s enjoyment of his property at night — specifically, his ability to sleep undisturbed in his own bed in his own house on his own rural property. The interference is intermittent, but ongoing. While Mr Zakula is annoyed by the sound of the turbines during the day, it does not substantially interfere with his enjoyment of his property.

[following consideration of the evidence given by Noel Uren, her Honour held]:

I find that wind turbine noise disturbed Mr Uren’s sleep, waking him or keeping him awake, or both, on around 100 occasions between May 2015 and December 2018. His sleep was disturbed by turbine noise on six separate nights before the land was sold in March 2016. The remaining disturbances occurred after the sale, while Mr Uren was still living in the house with the agreement of the new owner. I am satisfied that this amounted to a substantial interference with his enjoyment of the property at night. During the day, however, the turbine noise was annoying but bearable.

Mr Uren’s evidence was not controverted by Mr Turnbull’s conclusion that wind turbine noise measured at the southern Uren property in 2021 did not exceed 40 dB(A) at any wind speed.

[Her Honour then considered the conditions of the defendant’s planning permit, which depend on the (thoroughly irrelevant NZ noise Standard) and the truly risible efforts made by the operator’s pet acoustic consultants, Marshall Day Acoustics to conjure up evidence that the noise levels generated by the turbines satisfied that Standard. Sensing that it was better to stay schtum, the operator kept MDA’s so-called experts well away from the courtroom; none of its staff or employees were called to back up the claims that they had made in their reports claiming compliance with the NZ Standard. Funny about that!. Instead, they called Chris Turnbull to gloss over the fact that enormous tracts of noise data had been deleted (MDA, Turnbull and their ilk call it ‘filtering’). Rejecting Turnbull’s sophisticated efforts to manipulate the data and distort the meaning of the NZ Standard, her Honour held]:

I do not accept that Mr Turnbull’s conclusions demonstrated compliance with condition 19(a) at Mr Zakula’s house or at Mr Uren’s former house, because he did not use the method for assessing wind farm noise prescribed by the NZ Standard, as required by condition 19 of the permit. The method prescribed by the NZ Standard is to derive wind farm noise levels by comparing the background sound level regression line with the regression line for the operational wind farm.

I am also unable to accept Mr Turnbull’s opinion that MDA’s reports demonstrated compliance with condition 19(a) at the plaintiffs’ houses.

…

By contrast, the MDA Zakula noise report and the MDA Uren noise report were based on operational noise monitoring data recorded at the relevant locations. As discussed, MDA reached the remarkable conclusion that the noise levels at both residences were lower overall than the background levels used for comparison. No-one from MDA was called to explain these findings. They were plainly not tenable. It is simply not possible that it became quieter at either Mr Zakula’s house or Mr Uren’s house after the wind turbines started operating in March 2015.

[In the passage above, her Honour notes the peculiar ability of wind industry acoustic consultants to obtain lower recorded noise levels at neighbour’s homes AFTER a wind farm is built and wind turbines start operating. Earlier in the reasons (at [108]-[110]) her Honour showed their slight-of-hand magic at work]:

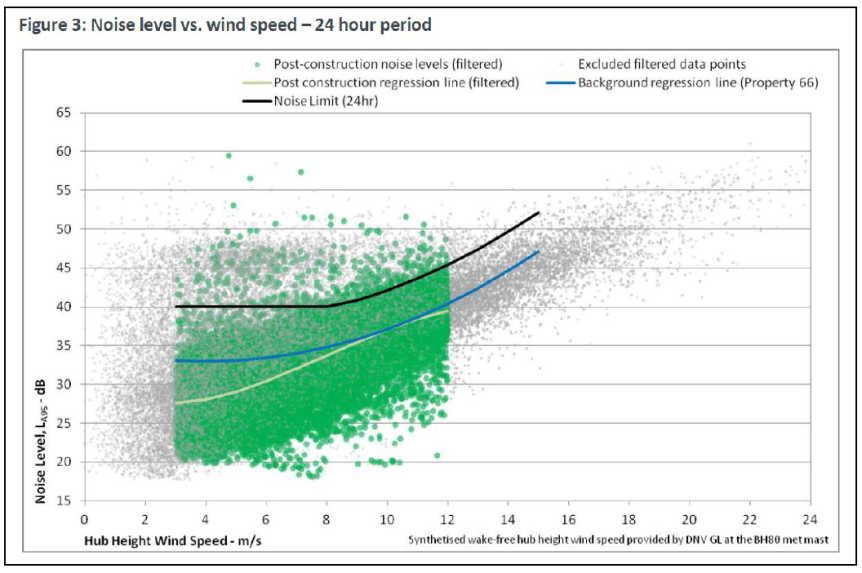

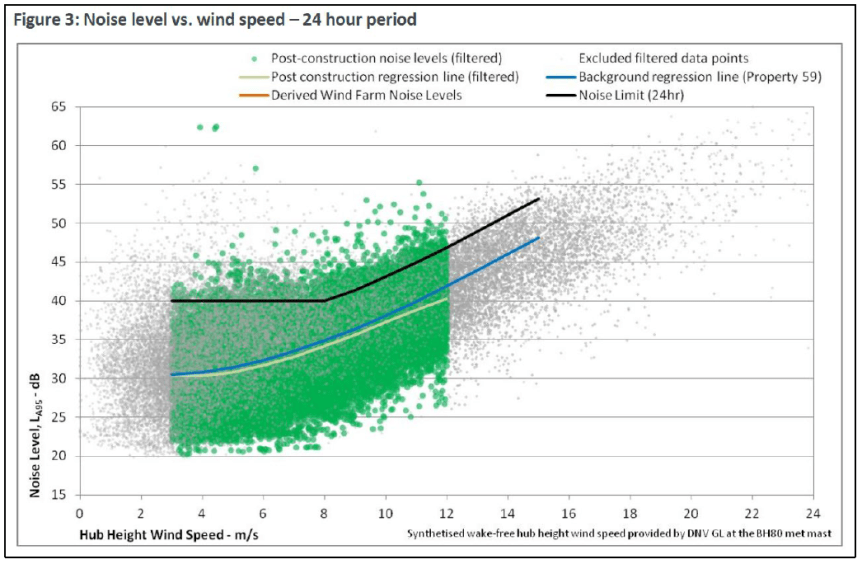

Remarkably, MDA concluded that post-construction noise levels at both properties over a 24 hour period were lower than the pre-operational background noise levels used for comparison. These findings are illustrated in Figure 3, in relation to Mr Zakula’s property and Figure 3, for Mr Uren’s house:

Figure 3: Graph showing noise level vs wind speed measured over a 24 hour period at Mr Zakula’s property, from the MDA Zakula noise report, page 21.

Figure 3: Graph showing noise level vs wind speed measured over a 24 hour period at Mr Uren’s property, from the MDA Uren noise report, page 21.

The derived wind farm noise levels — that is, the difference between the measured post-construction noise levels and the background noise levels — are not shown on either graph. That is presumably because the post-construction noise levels were lower than the background noise levels in both cases.

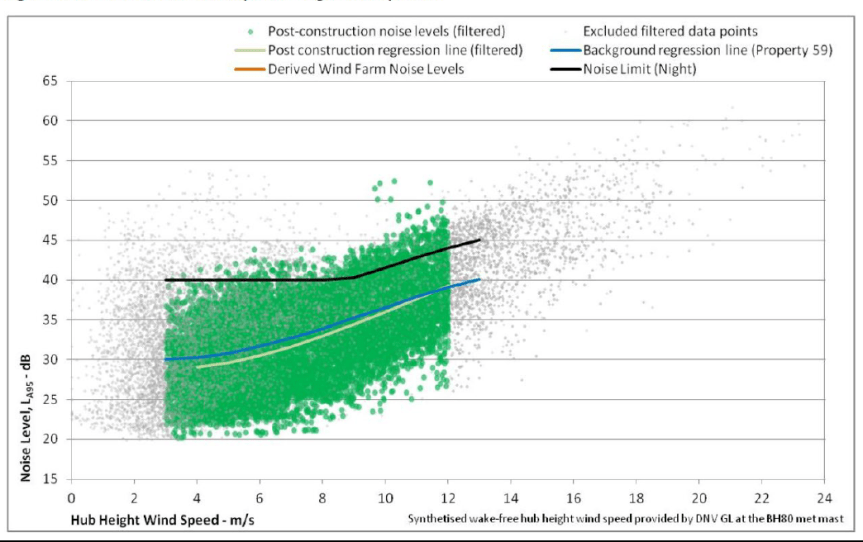

For the night time period, MDA concluded that post-construction noise levels were lower than pre-operational background levels at Mr Zakula’s property at wind speeds below 8 m/s, and at Mr Uren’s property at wind speeds below 11 m/s. These findings are illustrated in Figure 4 and Figure 5 respectively.

Figure 4: Graph showing noise level vs wind speed measured over the night time period at Mr Zakula’s property, from the MDA Zakula noise report, page 21.

Figure 5: Graph showing noise level vs wind speed measured over the night time period at Mr Uren’s property, from the MDA Uren noise report, page 21.

The invalidity of MDA’s conclusions in these two reports may have resulted from one or more of the following matters:

(a) No background sound level measurements were taken at either house. The background measurements used for comparison were taken at different locations — at House 66 in Mr Zakula’s case, and at House 59 in Mr Uren’s.

(b) The background sound level measurements were taken during construction of the wind farm. It is possible that the sound levels recorded were affected by construction activities, including heavy vehicles on Buffalo-Waratah Road.

(c) MDA applied data filtering to the noise monitoring data recorded at both houses between late 2015 and September 2016, as described at [115] above, including filtering for extraneous noise. MDA did not explain in any of its reports what, if any, filtering it applied to the data recorded when background sound level measurements were taken. I heard no evidence from anyone at MDA, and I am not confident that it filtered its pre-construction data in the same way as its operational noise monitoring data. I am not reassured by Mr Turnbull’s opinion that it did, for the reasons given at [184] below.

(d) There was a high level of uncertainty about the accuracy of the wind speed data used by MDA in its analysis. This was exacerbated by the failure of both of the top-mounted sensors on the BH80 wind monitoring mast, the second of which failed in August 2016.

(e) MDA included data recorded when at least 50 of the 52 turbines were in operation. It does not appear to have paid attention to which turbines were not operating. Data gathered when one of the turbines close to Mr Zakula’s house was not operating — in particular turbine 16 — would not fairly represent typical wind farm noise levels there. The same would apply to noise levels recorded at Mr Uren’s house when one of the nearby turbines was off, inparticular turbine 42.

It is not necessary to make any finding about why MDA’s assessments of wind farm operational noise at Mr Zakula’s and Mr Uren’s properties went astray. The findings MDA expressed in both reports are obviously unsound, and do not demonstrate permit compliance at either property.

[The more likely cause is that MDA did what it always does: it placed its noise loggers close to large trees and/or under bushes during pre-construction noise data gathering (thereby raising the average noise levels at all wind speeds) and, when it returned to gather operational noise data, it placed its noise loggers well away from trees, bushes and other solid objects (thereby lowering average noise levels at all wind speeds, even with the contribution from wind turbines, if, indeed, any of them were, in fact, operating at the time). It’s the oldest trick in the book and it’s been used by MDA and others for years, all over Australia. The other clever trick played by the operator, in this case, was withholding the raw data from the plaintiffs’ acoustic experts, Dr Bob Thorne and Les Huson. Whereas, they were happy to provide the raw data to their own boy, Chris Turnbull, the plaintiffs’ acoustic experts were deliberately deprived of the opportunity to assess and review that data. Her Honour was scathing about that conduct]:

The questions explored during the experts’ evidence included what filtering was applied by MDA to its background and operational sound level measurements used to assess compliance with condition 19(a). Dr Thorne and Mr Huson both said that they did not know how MDA had filtered its background data, because they had never seen MDA’s datasets. Mr Turnbull volunteered that he had asked for and analysed the raw background data for locations 19, 61 and 66, and had satisfied himself that they had applied the same filtering to both pre-construction and operational data. Dr Thorne was ‘stunned’ to learn that this raw data had been given to Mr Turnbull, when he had asked for the same information 18 months previously and it had never been provided. The raw background data was apparently not discovered by Bald Hills, or produced by MDA in answer to a subpoena served on it in May 2020. The raw data files were belatedly produced by Mr Turnbull during the trial, in response to a subpoena for production served on him in June 2021. It is unsatisfactory that Dr Thorne and Mr Huson did not have timely access to relevant data, and had no opportunity to analyse it while preparing their reports or before giving evidence. In those circumstances, it would be unfair to the plaintiffs to accept Mr Turnbull’s opinion based on that data.

[Ouch!! Her Honour then went on to consider the woefully inadequate work by both MDA and Chris Turnbull in relation to the assessment of Special Audible Characteristics, such as tonality. The findings and conclusions at [185]-[193] were, again, damning. The reasons then focused on the NZ Standard which set the limits of noise in the operator’s planning permit. Her Honour, rejecting the operator’s claim to be compliant with that standard and the related noise condition, held]:

I find that Bald Hills has not established that the sound received at either Mr Zakula’s house or Mr Uren’s house complied with the noise conditions in the permit at any time. The Minister’s letter of 23 March 2019 did not determine that question.

Bald Hills did not demonstrate compliance with condition 19(a) of the permit, either by Mr Turnbull’s assessment of the noise monitoring data he recorded in 2021, or his review of MDA’s noise assessments. Mr Turnbull’s method for assessing compliance with condition 19(a) was not the method prescribed by the NZ Standard, properly interpretedMDA initially did not assess compliance at Mr Zakula’s house or at Mr Uren’s house, but at other nearby locations. The noise assessments MDA conducted at both locations in 2015 and 2016 were plainly flawed.

I have concluded that neither Mr Turnbull nor MDA properly applied condition 19(b) in assessing compliance with conditions 19(a) and 19(c). … [T]heir subjective assessment of the presence of impulses and amplitude modulation was inadequate, particularly at night. They undertook no objective assessment of the presence of either of these special audible characteristics, which had been the subject of complaints from the plaintiffs

[Wind power outfits have always argued that compliance with the noise condition of their planning permits is a complete defence to a claim in common law nuisance seeking an injunction and/or damages. Her Honour held otherwise]:

There was a difference between the parties as to the significance of demonstrating compliance with the permit. Strictly speaking this issue need not be determined, given my conclusions in relation to permit compliance. It was common ground that failure to comply with the noise conditions in the permit would support a conclusion that the wind turbine noise was both substantial and unreasonable.

[Her Honour then discussed the authorities on that issue and the purported relevance of the noise limit set by the NZ Standard and noise condition in the planning permit and held that]:

If Bald Hills had been able to establish that it complied with the noise conditions in the permit at the plaintiffs’ houses, this would have given weight to its contention that the noise from the wind farm is at reasonable levels at both locations — even though Mr Zakula’s house is not an ‘existing dwelling’ for the purposes of the permit. Although permit compliance is not determinative, the noise limits set in the NZ Standard and applied by condition 19 of the permit are a benchmark that have brought some order to the debate However, I would also have taken into account that it is a matter of judgment whether 40 dB or 35 dB is an acceptable noise limit for rural dwellings at night, and that Victoria is the only Australian state that has adopted the higher limit.

More significantly, I would have considered that the NZ Standard sets a limit on the extent to which continuous underlying noise levels may be increased by wind turbine noise, assessed over weeks or sometimes months. It is not directed to intermittent loud noise from wind turbines, and provides no means of determining whether a wind farm produces unreasonably annoying noise in certain weather conditions, or on a particular night. Demonstrated compliance with the NZ Standard and condition 19 would not necessarily have established that the noise that from time to time disturbed Mr Zakula’s and Mr Uren’s sleep was reasonable.

[The reasons then turned to the operator’s (thoroughly predictable) argument that its turbines generate ‘wonderful’ cheap and cheerful “renewable energy”. However, her Honour quite rightly held that a good night’s sleep in one’s own home trumps all]:

The evidence did not suggest, however, that there is a binary choice to be made between the generation of clean energy by the wind farm, and a good night’s sleep for its neighbours. It should be possible to achieve both — indeed, that is what condition 19(c) of the permit requires. Further, condition 22 of the permit contemplates that, in some weather conditions, the wind farm may have to noise optimise or selectively shut down some turbines to reduce noise to an acceptable level. There was nothing to suggest that this could not have been done in response to the complaints of Mr Zakula or Mr Uren, while continuing to generate renewable energy.

[Her Honour then went on to reject an argument that because the plaintiffs had opposed wind turbines being speared into their backyards they were “hypersensitive” to noise, and then turned to the evidence of other neighbours who, like the plaintiffs, have been tormented by wind turbine noise since they began operating in 2015. It is not only compelling it is heartbreaking testimony, which we set out in full]:

Evidence of neighbours

A number of witnesses were called to give evidence about their experience of noise from the wind farm. The plaintiffs called six former plaintiffs — Don and Sally Jelbart, Dorothy and Don Fairbrother, Alexander McDougall and Stuart Kilsby. They also relied on the evidence of Roberto Soler, who works for the Kilsby family as a resident farm manager. Bald Hills called its asset manager, Mr Furlong, as well as Darcy O’Halloran, a site supervisor, and Robert Anderson, a farm hand who lives near the wind farm.

Don Jelbart owns three separate properties near the wind farm: his home, a property located slightly to the south of his home, and Tenement A. His experience of noise from the wind farm varies, depending on his whereabouts. He said that when he is at home, he hears all manner of noises. He described feeling a ‘deep throbbing pulse’ from the wind turbines, or a ‘low groan that gets right into your head’. He said that he has on occasion got up out of his chair, thinking that a truck is coming up his driveway, only to realise that he is just hearing the sound from the wind turbines.

Mr Jelbart said that his experience is ‘much worse’ inside his home than outside, and is particularly bad at night. Sometimes, the turbines are louder than his television, even after he has turned the volume up. He often wears earplugs to bed, however he is still woken up during the night. He attributes this sleep disturbance — which he said he has experienced for about the last six years — to the noise from the wind turbines. He sometimes wakes up with a headache. In an attempt to block out some of the noise, he has moved to a room in the back of his house, and has planted some trees.

According to Mr Jelbart, the noise at Tenement A is ‘horrific during the day’. He said that if he has to spend a couple of hours there, he will either put in earplugs or leave the property altogether. He described the noise at Tenement A as a ‘pulsing throb’, sometimes with a ‘whoosh’, and often with a ‘gearbox noise’, a ‘grinding sort of mechanical noise’, which signals that there is a gearbox in need of attention. The noise varies depending on where he is on the property and which way the wind is blowing. Mr Jelbart said that although he can always hear the noise when the wind is blowing, it is particularly bad when the breeze is gentle and when the wind is coming from the south or the south-west. He said that the noise seems to be worse in the winter months.

Mr Jelbart agreed that he had lived in the area for most of his life and had been opposed to the wind farm for a long time. He had been the president of a community organisation call the Tarwin Valley Coastal Guardians, formed in about 2004, which had made submissions to the Panel about the permit and had also been involved in a proceeding at the Tribunal about an increase in the permitted height of the turbines. He agreed that he was staunchly opposed to the wind farm even being built, and opposed the grant of the permit on a number of grounds. His biggest concern was about the destruction of wedge-tailed eagles, a concern which had proved to be true. He agreed that the wind farm had divided the community, and that some friendships had come to an end.

Sally Jelbart also spends her time across several properties. She described the noise at Tenement A during winter as being like waiting at an airport with ‘a dozen planes around you and they are all, you know, waiting for their turn to go on to the runway. It’s loud.’ She said that she can hear the turbines at Tenement A at all times of the year, but that they sound different during summer. At Tenement A, the noise is ‘on top of you’ and sometimes, after spending a few hours there, she thinks ‘that’s enough, I need to go and work somewhere else, do something else’, and she has to leave to escape the noise.

Mrs Jelbart said that when she is at home at night, when the wind has died down, the sounds from the wind farm can be very audible — ‘it can be a thumping, a groaning, a whirring, a grinding; you can get all of these sounds in five minutes and then it’s just on repeat, on repeat, on repeat’. She described the noise as having ‘a deep undertone to it which really sort of — it sort of gets in your head. It just vibrates through you.’ Like Mr Jelbart, she can hear the turbines over the sound of their television, even if the volume is turned up high. The noise wakes her up regularly during the night and in the early hours of the morning. When she wakes up, she often has a headache. Because she experiences so much tension, she has taken to wearing a mouthguard to bed to protect her teeth.

Mrs Jelbart has been a vocal opponent of the wind farm since it was first proposed. She was a member of the Tarwin Valley Coastal Guardians, a group that was opposed to the wind farm. She was concerned about poor regulation and compliance in the wind industry, about the industrialisation of the landscape, and about the raptors and other big birds being injured by the turbines. She was also concerned about division in the community, and said that in fact the wind farm has divided those who have benefitted from it and those who have not.

Dorothy Fairbrother and her husband Don live and work on their farming property on Buffalo-Waratah Road, Tarwin Lower. The property is located between Mr Zakula’s house and where Mr Uren used to live. Mrs Fairbrother described the sound from the wind turbines as ‘a swishing, throbbing noise that just didn’t disappear’. She said that the noise is more prominent in the evening. It can be heard over the television at times, and so she turns up the volume of the television to camouflage the noise. She described the noise as being similar to ‘dripping tap syndrome’ that keeps ‘going and going and going’ at night time, and interrupts her sleep. She does not hear the noise every night. It is worst when the wind is blowing from the north-west, which occurs more in autumn and winter. During bad periods, which can last up to three weeks, her sleep is interrupted every night.

Mrs Fairbrother suffers from ‘bad headaches’ due to the noise of the turbines at night, for which she takes paracetamol and stronger medication when required. She does not take anything to help her to get to sleep – she tries to ‘just suffer it out’. She and Mr Fairbrother tried to alleviate the noise by double glazing the windows in their house, but that did not help a lot. Now they just keep the windows shut and the curtains drawn. They also spent three to four weeks sleeping in another bedroom, which made no difference.

While working outside on the farm, Mrs Fairbrother can hear a ‘throbbing’ noise that can become ‘mechanical’. The noise becomes more prominent closer to the turbines. Sometimes she has to turn her back on the turbines because she gets motion sickness.

Mrs Fairbrother agreed that she had opposed the approval of the wind farm, and had made submissions to the Panel to that effect. She was concerned about division in the community, between lifelong friends and family members, and environmental effects. She was not opposed to renewable energy; her concern was with siting the wind farm too close to where people are living.

Don Fairbrother has had long-term hearing problems. His hearing has deteriorated since 2015, and he has had a cochlear implant in his right ear since 2019. He uses a hearing aid in his left ear, which he takes out at night. Mr Fairbrother first noticed noise from the wind farm in March 2015, when he returned from a trip to Melbourne. He could not believe how loud it was. At that time, he could hear the noise without his hearing aid in.

The noise that Mr Fairbrother first heard from the wind farm was a very audible ‘whooshing noise and a thumping noise as the blade goes past the tower’. Inside their home, in the evenings, he could hear a ‘thumping’ and ‘pulsing’ noise. At night, with his hearing aid out, he could hear the noise but it was not as loud. He would wake up in the early morning with a really severe headache, and when he put his hearing aid in, he realised what was going on. When he woke at night with a headache he would take Panadol, but would always have trouble getting back to sleep. Even with his hearing aid out he was tossing and turning, having broken sleep, sensing the noise. Mr Fairbrother said that the noise is less audible in the summer period, and not the problem that it is in the wintertime.

His hearing has since deteriorated and now he cannot hear the wind farm noise at night when his hearing aid is removed. However, he is still woken at night intermittently by the wind farm.

Mr Fairbrother opposed the wind farm from the time it was first proposed. He made submissions to the Panel opposing the approval of the wind farm, and continued to oppose it after it was approved. His concerns included its effect on bird life, including the orange-bellied parrot and white-bellied sea eagles, as well as the impact on the visual amenity and value of his property. He has a poor opinion of the wind industry and the way in which it is regulated.

Alexander McDougall’s family company, The Firs Pty Ltd, owns two plots of land in the vicinity of the wind farm, in addition to a farm in Strzelecki. Before the construction of the wind farm, Mr McDougall’s parents had planned to build a house on one of those plots and he had planned to build a house on the other. He said that his family no longer plans to build on either property, because they could not live there and a house would not add value. He continues to live in Strzelecki, and spends six days a week farming the two properties in Tarwin Lower.

Mr McDougall splits his time evenly between farming the ‘northern property’ (also known as the Firs Tenement) and the ‘southern property’. When he is at the northern property, he hears different noises coming from the wind turbines. For example, he described hearing a ‘whoosh whoosh whoosh’ sound, and, sometimes, ‘a mechanical noise, almost like a metal cog or something that clanks’. He recalled times where he had been on his work phone in the paddock and had been unable to continue his conversation due to the sound coming from the wind turbines. The noise is affected by wind speed and direction, and there seems to be a lot more noise in July and August. Mr McDougall had, on occasion, spent the night at the northern property. On those nights, even though he was exhausted, he had been woken up due to the noise from the wind turbines.

The McDougalls’ northern property shares a boundary with Mr Uren’s former property. Mr McDougall said that when he is working the cattle yards in that corner of the northern property he can quite clearly hear a lot of noise from the turbines. He described hearing a ‘whirring noise’, which ‘can get in your head’, cause disorientation and headaches, and ‘doesn’t seem to go away’. Mr McDougall said that he had been inside Mr Uren’s house a number of times during the day while Mr Uren was living there. He could hear the sound of the turbines in the background while he was inside the house.

Mr McDougall’s experience of the noise coming from the wind turbines at the southern property is the same as his experience at the northern property. The noise is particularly bad at the top of the property and there are days when the noise up there is too much, and he looks for another job somewhere else on the property. There are spots on the southern property where he can go for some relief, and his motorbike can drown out some of the noise.

Mr McDougall did not actively oppose planning approval for the wind farm, being in his early 20s at the time. His late father was upset that the family could not build homes on the properties and move there to live.

Stuart Kilsby’s family lived on their farm in Tarwin Lower until they moved away in 2012 or 2013. Mr Kilsby’s father did not think they would be able to stay on the farm once the wind farm started operating due to the ‘noise issue’. Before then, Mr Kilsby had planned to build a house on the property, and had picked out a site overlooking the whole farm, with views of Bass Strait, the Inverloch inlet and Wilsons Promontory. He no longer plans to build that house. He now lives in Inverloch while working six or seven days a week on the farm in Tarwin Lower.

Mr Kilsby described a vibration and a ‘whistling’ noise, coming from five or six turbines, all operating at different times — he called it a ‘humming vibration sound’ in his ears. He said that the turbines are very loud but at different times, depending on which way the wind is coming from. Wind from the south-west or east makes the noise particularly bad. Mr Kilsby has slept at the farm a few times, mostly during the calving and lambing period, and has noticed that the wind farm noises are louder at night, when there is less interference from other noises that he usually hears during the day.

After the turbines started spinning, Mr Kilsby’s father could not handle the noise and left the farming to his son. Mr Kilsby felt anxious to come and work at the farm, knowing that he would be hearing the noise all day. At the farm, he struggled to concentrate. He had difficulty getting the noise out of his head, even after leaving the farm. Sometimes, he had to leave the farm when the noise became really bad. He used to take his wife and young children to the farm for camping or picnics, but he no longer does this because he is concerned about the noise from the turbines.

Mr Kilsby was a teenager when planning approval was sought for the wind farm. He was aware that his father had opposed the approval, because he did not want the wind farm so close to the family’s farm, and thought that the noise from the turbines would be a nuisance. Mr Kilsby recalled his father also being concerned about the farm losing value and adverse effects on bird life in the area, and he shared those concerns. He agreed that, by the end of 2018, he wanted the wind farm to shut down — ‘anything to get the noise to stop’.

Roberto Soler is employed by the Kilsby family as a farm manager. He worked on the farm for a few months in 2014, and then returned in 2018. He now lives in the farmhouse on the Kilsby property, where he also stayed in 2014.

Mr Soler said that when he is out farming during the day, he can hear sounds coming from the wind turbines. He said that what exactly he hears depends on the wind and his proximity to the turbines. When it is windy, the sound is louder. When there is no wind, he does not hear anything. He described the louder sounds as being like, ‘when you are beside a road busy of cars, you know, traffic or a river, something like that.’ He said that, when the sound is loud, he will often have trouble hearing what other people are saying, and will have to raise his voice, call the person or send them a text message. He said that the noise is worse when the wind is blowing from the east. The noise gets in his head and is constant; he gets ‘tired with that because it’s all the time the same noise’.

When Mr Soler is inside the farmhouse, he finds the noise annoying when he is trying to read a book. However, it is not so bad when the television is on. The noise is worst at night, when the house is quiet. The worst thing is that the noise is constant. In 2014, when he was staying at the property, he slept well. Now, he has trouble falling asleep due to the sound coming from the turbines. It can take him one hour or more to fall asleep. He said that his partner, Katherine, has told him that the noise from the turbines has woken her up in the middle of the night.

…

Having considered this evidence as a whole, I do not consider that Mr Zakula and Mr Uren are hypersensitive to noise from the wind farm. I accept that Mr Uren’s negative attitude to the wind farm increased the degree to which he was annoyed by noise from the turbines. However, I do not regard his reaction as excessive or unreasonable. It is in keeping with his neighbours’ experience of wind farm noise. Unlike Mr Uren, Mr Zakula did not have any predisposition against the wind farm before it started operating. His antipathy to it stems from persistent noise that disturbs his sleep, and the way in which the wind farm has responded to his complaints.

[Her Honour then dealt with, and dismissed, a series of arguments run by the operator to the effect that its soul-destroying noise was “reasonable”; and that it had taken “precautions” by investigating complaints and pretending to ensure compliance with the noise limits in its planning permit. Her Honour rejected them all, and held that the noise generated constituted an unreasonable interference with the use and enjoyment of the plaintiffs’ homes. Her Honour concluded]:

Issue 11 – An unreasonable interference?

My conclusions in relation to issues 3 to 10 are, in summary:

(a) Noise from the turbines on the wind farm disturbed Mr Zakula’s sleep on hundreds of occasions since the wind farm began operating in 2015. Wind turbine noise disturbed Mr Uren’s sleep on around 100 occasions between May 2015 and December 2018. This amounted to a substantial, albeit intermittent, interference with the acoustic amenity of the plaintiffs’ properties at night. In Mr Zakula’s case, the interference is ongoing.

(b) Bald Hills did not establish that the sound received at either Mr Zakula’s house or Mr Uren’s house complied with the noise conditions in the permit at any time.

(c) Even if Bald Hills had been able to establish compliance with the noise conditions in the permit at the plaintiffs’ houses, this would not have been determinative of reasonableness. The noise limits under the permit and the Environment Protection Regulations are at the higher end of the range applied in Australia. Significantly, while the NZ Standard and condition 19(a) limit the extent to which continuous underlying noise levels are increased by wind turbine noise, they are not directed to intermittent loud noise from wind turbines, and provide no means of determining whether a wind farm produces unreasonably annoying noise in certain weather conditions, or on a particular night.

(d) The wind farm makes a substantial contribution to Australia’s renewable energy industry, and to efforts to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and limit the effects of climate change. This is a socially valuable activity, and it is in the public interest for it to continue. However, there was no evidence that the wind farm could not continue to operate while also reducing the noise from some turbines to a reasonable level.

(e) Neither Mr Zakula nor Mr Uren are hypersensitive to noise from the wind farm.

(f) The locality is rural, relatively quiet, and remote. Sounds associated with stock rearing, grazing and other farming activities are typical of the area during the day. These activities do not cause intrusive noise at night. Traffic on nearby roads is light and usually creates limited disturbance. Because Bald Hills has not shown the wind farm to comply with the noise conditions in the permit, I have not considered the wind farm as one of the established uses in the locality.

(g) The precautions taken by Bald Hills were to investigate and respond to the numerous complaints made by Mr Zakula and Mr Uren. No remedial action was taken by Bald Hills to reduce the noise from the wind turbines received at either property. While some remedial action was taken to reduce noise levels at other locations, this was not shown to achieve compliance with the noise conditions in the permit at the plaintiffs’ properties.

(h) There are two other precautions that Bald Hills could reasonably have taken. It could have followed the procedure contemplated in condition 22 of the permit and selectively noise optimised or shut down relevant turbines to reduce noise levels at the plaintiffs’ properties at night and during certain weather conditions. It could also have addressed the gearbox tonality issue identified by MDA in December 2016. Neither has been done.

Having regard to all of these matters, I find that noise from the wind turbines on the wind farm has amounted, intermittently, to a substantial and unreasonable interference with Mr Zakula’s enjoyment of his land at night. I reach the same conclusion about the effect of wind turbine noise at Mr Uren’s house until December 2018. The wind farm noise has been a common law nuisance at both properties at night.

Issue 12 – A continuing nuisance?

Bald Hills accepted that, if it was found to be causing a nuisance at Mr Zakula’s property, an intermittent interference with his acoustic amenity would continue at night. In other words, it accepted that the nuisance would continue. It also accepted that Mr Zakula would be entitled to some relief.

[Her Honour then turned to the remedies sought by the plaintiffs, namely an injunction preventing the operator from running its turbines at night time while they, and their neighbours, are attempting to sleep, and damages for the decline in the value of their properties, and for the distress, inconvenience and annoyance caused by the nuisance. They also sought aggravated and exemplary damages. Her Honour noted that the principal remedy for nuisance is an injunction restraining the party causing it, as well as damages for the nuisance caused before the injunction takes effect. Her Honour awarded an injunction, but decided to stay the operation of the injunction for three months to allow the operator an opportunity to attempt to abate the nuisance; that is, to either selectively shut off turbines, soundproof the victims’ homes and fix the tonal noise generated by the turbines, which had been identified years before. Her Honour held]:

The nuisance has been ongoing and unabated since 2015, and Mr Zakula should not have to endure another winter in which his sleep is disturbed by excessive wind turbine noise.

I will grant an injunction restraining Bald Hills from continuing to permit noise from wind turbines on the wind farm to cause a nuisance at Mr Zakula’s house at night, and requiring it to take necessary measures to abate the nuisance. The injunction will be stayed for three months.

[After three months, the operator will be subject to the terms of the injunction, preventing it from operating its wind turbines at night, when people are trying to sleep – as is their lawful right. As that was the plaintiffs’ principal complaint, the scope for awarding damages for future loss of amenity, distress, inconvenience and annoyance was necessarily reduced; their ability to sleep in, use and enjoy their homes will be restored 90 days from judgment, by operation of the injunction. The plaintiffs sought aggravated damages for the operator’s high-handed disregard of their, entirely legitimate, complaints. Her Honour reasoned on that issue as follows]:

Issue 21 – Aggravated damages

The plaintiffs also sought aggravated damages, on the basis that Bald Hills knew or ought to have known that it was causing an unlawful nuisance. It was common ground that aggravated damages are compensatory, and may be awarded when the harm done by the defendant’s wrongful act was aggravated by the manner in which it was done. While Bald Hills drew attention to historical doubts as to whether aggravated damages were available for nuisance, it accepted that they could be awarded in an appropriate case, for example where the defendant’s conduct was ‘of such a high-handed nature that it merited aggravated damages’.

In my view, Bald Hills’ conduct towards Mr Zakula and Mr Uren has been of that nature. They both repeatedly complained that noise from the wind turbines at their homes was disturbing their sleep. Mr Uren first complained in May 2015, while Mr Zakula did not formally complain until September 2015. Bald Hills never responded to either man’s complaints by trying to reduce wind turbine noise at their homes. Rather, it denied that they had any cause for complaint, minimised their lived experience of the noise, and treated them as hypersensitive trouble-makers. In 2017, it accepted and relied on MDA’s patently absurd conclusions that it was quieter at both properties after the wind farm started operating. The evidence of both Mr Zakula and Mr Uren left me in no doubt that, over time, they found the lack of any remedial action by Bald Hills to be frustrating and deeply discouraging. I accept that this compounded the effect of the noise nuisance that intermittently kept them awake at night.

When Mr Zakula, Mr Uren and others took their concerns to their local council, Bald Hills engaged lawyers and consultants who flooded the Council with submissions and reports that did not engage with the substance of the complaints. After the Council determined that the wind farm noise was causing an intermittent nuisance at properties including Mr Zakula’s and Mr Uren’s, Bald Hills sought judicial review of the Council’s resolution in this Court. The litigation, while ultimately unsuccessful, was a source of stress for both plaintiffs. Mr Uren found it terribly upsetting, and felt that Bald Hills was ‘treating the little people like rubbish’. Overall, Bald Hills’ response to the complaints to the Council was strikingly disproportionate, and did nothing to mitigate the noise nuisance at the plaintiffs’ homes. I am satisfied that it further aggravated the loss of amenity suffered by both plaintiffs in their homes.

The vigour with which Bald Hills disputed the complaints to the Council would have been better directed to finding a solution to the gearbox tonality issue first identified by MDA in December 2016. MDA advised Bald Hills at that time that it should identify an engineering solution to mitigate tonal emissions for specific turbines, rather than continue to rely on noise optimisation to achieve compliance. It is yet to do so. Its delay in finding a solution is largely unexplained, it being unclear why nothing was in place before Senvion went into voluntary administration in April 2019. Bald Hills’ ongoing failure to fix the known tonality issues in turbines 16 and 23, closest to Mr Zakula’s house, amounts to seriously high-handed treatment of him.

At one point during cross-examination of Mr Zakula, counsel for Bald Hills put to him that ‘give and take’ is important between neighbours. While that is undoubtedly true, it is difficult to see what Bald Hills has given in response to Mr Zakula’s complaints over a period of more than six years. Mr Arthur’s belated offers in December 2020 and March 2021 to discuss acoustic treatments at Mr Zakula’s property were, as I have found, not well directed. A reasonable neighbour would have tried to reduce the noise; Bald Hills has not.

I consider that the manner in which Bald Hills has dealt with the plaintiffs’ reasonable and legitimate complaints of noise has, over many years, at least doubled the impact of the loss of amenity each of them has suffered at their homes. On that basis, I award aggravated damages of $84,000 to Mr Zakula, and $46,000 to Mr Uren.

[While apparently tempted to order exemplary damages – because the operator knew about the annoying tonal noise generated by its turbines for years, but flatly refused to do anything about it – her Honour declined to order exemplary damages. Her Honour then quantified the plaintiffs’ damages and made the final orders, as follows]:

Issue 23 – Proper measure of loss and damage

In summary, the proper measure of Mr Zakula’s loss and damage is $168,000, comprising $84,000 for past loss of amenity, and an additional $84,000 for aggravated damages. Had I not decided to grant an injunction requiring Bald Hills to abate the nuisance, I would also have awarded Mr Zakula $200,000 as compensation for the reduction in value of his property as a result of the nuisance.

The proper measure of Mr Uren’s loss and damage is $92,000, comprising $46,000 for past loss of amenity, and an additional $46,000 for aggravated damages.

DISPOSITION

There will be judgment for the plaintiffs in the following terms:

(a) Bald Hills will be restrained from continuing to permit noise from wind turbines on the wind farm to cause a nuisance at Mr Zakula’s house at night, and will be required to take necessary measures to abate the nuisance.

(b) The injunction will be stayed for three months.

(c) Bald Hills is to pay damages to Mr Zakula in the sum of $168,000, comprising $84,000 for past loss of amenity, and $84,000 for aggravated damages.

(d) Bald Hills is to pay damages to Mr Uren in the sum of $92,000, comprising $46,000 for past loss of amenity and $46,000 for aggravated damages.

I will hear the parties on the questions of interest and costs.

It is not an overstatement to suggest that this judgment has entirely altered the landscape for the wind industry’s victims. Its consequences will reverberate around the world, for years to come.

Over the next few posts, we will concentrate on the immediate consequences for the Australian wind industry, which is already in a state of fear and panic. The pro-renewable propaganda squad in the mainstream press is in apoplexy.

For now, please make sure everybody you know knows about what Noel Uren and John Zakula have done to restore decency and humanity to rural communities, everywhere.

A huge congratulations to Noel Uren and John Zakula, the legal team and those who supported Noel and John. It took guts to take such action. Full of admiration.

Let’s raise our glasses as well to the late Peter Mitchell AM, who established the Waubra Foundation to help Fight These Things on the basis of deleterious health effects on the neighbours. A principle now firmly established in Australian law by Justice Melinda Richards of the Victorian Supreme Court.

Fight them Peter did, despite simultaneously fighting a degenerative health condition that eventually overwhelmed his life in 2020.

Well done, old friend.

Falmouth Massachusetts USA – Town-owned wind turbines shut down over noise nuisance June 2017 —

That was a victory, but not in common law nuisance. The 2 turbines were shut down by a local government zoning panel.

Though they were “shut down” they remained standing for a while and there was an issue about aviation safety (not avian). I contacted the town of Kingston administrator Tom Calter directly to inquire on the cost they are paying for keeping the mandatory aviation warning lights blinking all night long. He replied $1,000 per month until they remove the structures.

https://horsepower.net/decommissioned-turbines-require-electricity-from-grid-stay-on.html

The zoning board’s decision, that the turbines created a nuisance, was upheld, as was its decision that one of the 2 turbines did not have a valid permit

Reblogged this on Tallbloke's Talkshop and commented:

One in the eye for wind farm racketeers.

Outstanding! From your American cousins you can be sure we will add this to our arsenal against the wind industry here in the states. Thank You for your hard work and dogged determination – it’s greatly appreciated by all of us who are in the fight against this monstrous, corrupt and health damaging industry

In the theme of fighting for our human rights and balance there is another interesting Supreme court decision this one is from Germany where Dr. Stefan Lanka proved in 2018 that the measles virus does not exist. The case has undermined all “legal basis” for mandatory vaccinations around the world. Obviously many in official positions of policy did not get the memo or sent it to one of these towering bird shredders to dispose of it.

Well done to all those fearless people who had the will,strength, tenacity and first class legal acumen to get this landmark Case to such a marvellous outcome. Hopefully this decision will embolden many other Rural residents not just in Australia but across the World who have had their once peaceful, productive lives ruined by having Useless Noisy Oil Leaking Subsidy Sucking Wind turbines planted too close to their places of abode to rise up against this most corrupt and unscrupulous industry. All aided and abetted by brainless politicians who think that somehow they can spend $Billions of Other People’s Money to solve an nonexistent problem. Rural residents all around the World have for far too long been swept aside as “Road Kill” by the rampant intrusion of RE Rentseeking Windweasles whose main concern is for the “Climate” of their Bank Accounts.

A stunningly good judgement, STT and hats off to the two guys for pursuing the case right through to the end.

Thanks to you, too, for getting it out so quickly and for your clear comments against the extracts of the judgement.

I have just picked it up via https://www.facebook.com/WindEnergysAbsurd – word is going round the world

Fantastic outcome. This is a landmark case that sets a clear precedent for noise nuisance victims’ rights. And shines a light on the dodgy, high-handed practices of the wind farm industry. Congratulations and thank you to Noel and John for being so courageous. Congratulations to Dominica Tannock on her tenacity and thorough litigation work.

Finally, let’s hope we can shut the noisy vibrating Macarthur turbines down at nights and weekends. Hopefully the mortlake south turbines won’t ever get a start. But the six gutless lying moyne Shire councillers this term and last terms will blame the only counciller jim doukas who has listened and stuck up for us over the life of the Macarthur turbines. Same as Andrew dyer who sucked us in and abused our trust. Even tried to advise a judge which is contempt who promptly rebuked him. Wonder if he got his Melbourne club membership. I’m sure Malcolm trunball nominated him. Maybe after all these years we will finally get justice.